16 Working in Solidarity

Lessons Learned from Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective

Mercedes Jackson

Introduction

I am a feminist, and that means as much to me as my blackness;[1] it means that these two things can never be separated nor misconstrued. My lived experiences as a young, Black woman in America, has revealed the intricacies of our sociopolitical system. I have sat alone in too many classrooms as both the only Black person and Black woman. I have been subjected to too many microaggressions based on my skin color, socioeconomic status, or gender. For years, I have known that this society was not built with me in mind yet, it does not diminish my love for it nor my desire for it to change.

The recognition of the unique experiences of Black women have often been overlooked or ignored. For a long time, no space existed for Black women to think critically about their status in society that included both their race and gender. Caught between multiple and interconnected systems of marginalization and oppression, Black women developed their own politics and means of resistance: Black feminism.

As a framework, Black feminism conceptualizes the intersections of gender, sexuality, and race to acknowledge, and affirm the struggles of Black women throughout history.[2] If there is one thing I believe to be true, it is that Black women deserve better. Black feminism emerged out of this belief, as it was not enough to simply say that we were oppressed, we had to do more.

Combahee River Collective

Over forty years ago, the Combahee River Collective wrote their statement which introduced terms such as “interlocking oppression” and “identity politics.”[3] The Combahee River Collective (CRC) was a radical Black lesbian-led feminist organization formed in 1974. The collective was founded on a shared belief that Black women are inherently valuable, that our liberation is a necessity because of our need as human beings for autonomy.[4] For the next 7 years, the collective worked diligently to build a politics that was intersectional, radical and by all means, accessible to everyone who wished to join.

Named after Harriet Tubman’s raid on the Combahee River in South Carolina that freed 750 enslaved people,[5] the CRC was very influential in Black feminism. There was a need to develop a politics that was “anti-racist, unlike those of white women, and anti-sexist unlike those of Black and white men.”[6] There was work to be done in terms of activism, movement building and an overall analysis of our positions. It was apparent that the only people who cared about Black women were Black women. [7] The most profound concept of resistance is self-love which is to say that we as Black women matter and we know that we deserve better than what we have currently.

Analysis

Intersectionality

A combined anti-racist and anti-sexist position drew the founding members of the Combahee River Collective initially, and as they developed politically, the CRC addressed several issues concerning heterosexism and economic oppression under the capitalist system. [8] In their statement, the CRC believed that sexual politics under patriarchy was just as “pervasive in Black women’s lives as are the politics of class and race.” [9] It is difficult to separate the three because they are most often experienced simultaneously.

Not a day goes by that marginalized individuals do not feel the weight of their oppression. How we combat all the ways this shows up is both impossibly and possibly concrete. Black women’s negative relationship with the American political system has always been determined by our “membership in two oppressed racial and sexual castes.” [10] Recognizing that we as marginalized persons have the right and responsibility to analyze our positions in society as a part of a radical perspective. [11]

By believing this to be true, the CRC taught us that no group gets left behind; if we are to combat all forms of oppression, we must acknowledge and dismantle all the systems we participate in whether knowingly or unknowingly.

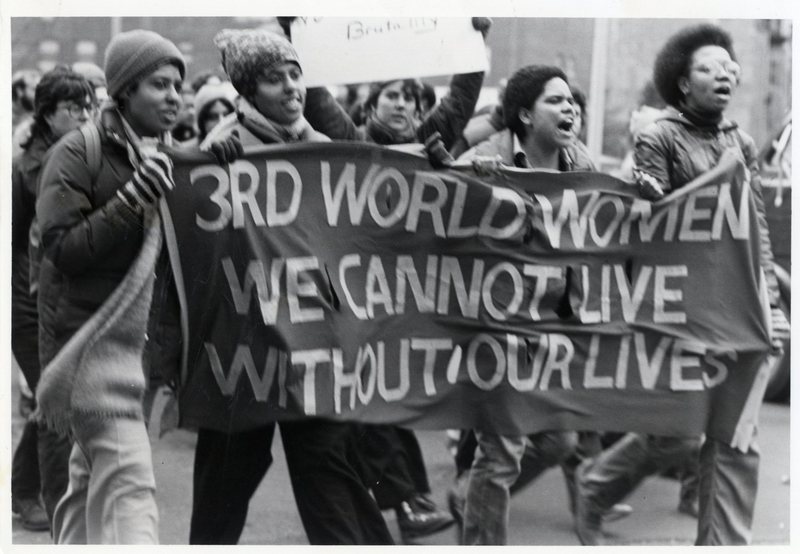

Internationalism

Before the term “women of color” existed, there was “third world women.” Before the 1980’s, “people of color” and “women of color” did not exist as terms and when it emerged, used only on the West Coast. In solidarity and in the struggle with all third world people around the globe, the Combahee River Collective aimed to be as inclusive as possible. One of the things that set the CRC apart from other groups at the time was their internationalism. [12] Barbara Smith, one of the founding members of the CRC, saw that Black women were being internally colonized within the United States. [13] And so were others, particularly, women around the world. From this stance, it is essential to think about building relationships and working in solidarity with everyone who has a stake in social justice. When a group gets left behind, the vision of the work gets trapped and is no longer viable as a goal.

Identity Politics

The “personal is political.”[14] Systems of oppression impact marginalized individuals in many ways such as sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, and racism. The Combahee River Collective believed that the most profound and radical politics come directly out of “our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody’s else’s oppression.” [15] In the case of Black women, this a particularly revolutionary concept that predates the term Black feminist. There is a legacy of dozens of women who have documented, theorized, and fought for the intellectual space of individual Black women’s lives. [16]

The major source of difficulty in the CRC’s work is that they were not just “trying to fight oppression on one front or even two, but instead addressed a whole range of oppressions.”[17] As such, the group did not even have minimal access to resources that groups who shared similar identities had. [18] In such conditions, the main goal of the Combahee River Collective was to raise the collective consciousness of society.

As a Black lesbian led organization, the question of whether Lesbian separatism was an adequate political analysis and strategy, impacted how progressive the collective wished their work to be. In their statement, they wrote that “even for those who practice it,” Lesbian separatism casts out far too many people – “since it so completely denies [anything] but the sexual sources of women’s oppression.” [19]

As socialists, the collective believed that the destruction of political-economic systems of capitalism and imperialism needed to be abolished. In such systems at the time, Black women were marginal in the labor force and doubly viewed as tokens at white-collar and professional levels. Articulating this double standard required that racial and sexual oppression were determinants in their working/economic lives. [20] Building from an anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist standpoint, the CRC found socialism to be the gateway for transformative justice. One of the shortcomings of focusing solely on the effects of racist, gendered, and sexualized violence, we tend to miss the underlying dynamics of class exploitation. [21] This critical analysis of their status in society was a marker of difference between the CRC and other groups.

In the totality of what it meant to be a Black woman in the diaspora, [22] the politics of the Combahee River Collective introduced the notion that we are multilayered people. As such, we have both the right and responsibility to build and define a political theory and practice upon that reality [23] that work towards liberation.

Coalition Building

If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since “our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.” [24] The inclusiveness of CRC’s politics makes them concerned with any situation that infringes upon the lives of women, the Third World, and working-class people. [25] Recognition that everyone especially those holding marginalized identities has a stake in social justice is one of the most fundamental building blocks of movement-building. Issues and projects that CRC’s members worked on include sterilization abuse, abortion rights, battered women, rape and healthcare which they collaborated with a few socialist feminist unions.[26]

All in all, Black feminism teaches that this kind of work does not get done alone, it takes the collective effort of individuals, leaders, and their communities to transform society.

Conclusion

In the decades since the establishment of the Combahee River Collective, the statement of Barbara Smith, Beverly Smith, and Demita Frazier has lived on. The fact remains that oppression based on identity is a source of political radicalization.[27] Black feminism has become a framework for acts of resistance in combating the oppression of trans women of color, the fight for reproductive rights, and the movement against police violence.[28]

As Black feminists and lesbians, the collective knew that they had a “very definite revolutionary task to perform” and were “ready for a lifetime of work and struggle.” [29] An important thing to note is that sometimes the end does not always justify the means. Members of the CRC believed that many reactionary and destructive acts have been committed in the name of “correctness.” There must be a collective process and nonhierarchical distribution of power within groups and within the vision for a revolutionary society. [30]

Contemporary Black feminism is the “outgrowth of countless generations of personal sacrifice, militancy, and work by our mothers, and sisters.” [31] In the minds of Black women everywhere, a revolution does not appear out of thin air; it is not achieved through superficial and individualistic means. The Combahee River Collective carved an approach that was multifaceted in aspect to their identities as Black lesbians, and conditions in a larger political framework.

There needs to be a collective consciousness rather than an individualistic one to combat all systemic oppression and marginalization. If we stand in solidarity with all marginalized groups, alongside our shared histories, the world has no choice but to change.

Mercedes is a third-year student majoring in Psychology and double minoring in Health and Human Services and American Ethnic Studies.

- Jordan, June. “Civil Wars.” (Scribner’s, 1996), 142. ↵

- Lindsey, Treva B. “Ula Y. Taylor’s ‘Making Waves: The Theory and Practice of Black Feminism.’” Black Scholar 44, no. 3 (Winter 2014): 48–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.2014.11641240. ↵

- Taylor, Yamahtta Keenaga. “How we get free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective.” (Haymarket Books, 2017), 4. ↵

- Combahee River Collective. “The Combahee River Collective Statement.” (Zillah Eisenstein, 1978), 3, https://americanstudies.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/Keyword%20Coalition_Readings.pdf. ↵

- Leichner, Helen. “Combahee River Raid (June 2, 1863),” December 21, 2012. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/combahee-river-raid-june-2-1863/. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 3. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 4. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 3. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 4. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 1. ↵

- Taylor, How we get free, 117. ↵

- Taylor, How we get free, 44. ↵

- Taylor, How we get free, 45. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 5. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 3. ↵

- Lindsey, Ula Y. Taylor’s ‘Making Waves: The Theory and Practice of Black Feminism, 48. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 7. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 7. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 6. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 5. ↵

- Hamer, Jennifer, and Helen Neville. "Revolutionary Black Feminism: Toward a Theory of Unity and Liberation." The Black Scholar 28, no. 3/4 (1998): 22-29. Accessed November 7, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41068802. ↵

- Taylor, How we get free, 121-122. ↵

- Taylor, How we get free, 61. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 7. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 7. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 11. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 8. ↵

- Taylor, How we get free, 13. ↵

- Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 11. ↵

- Taylor, How we get free, 11. ↵

- Taylor, How we get free, 2. ↵