Appendix 2: Gendered Violence in Puerto Rico

An Examination of Past and Present Acts of Aggression Against Women

María Fernanda

Introduction

As a woman in her twenties, I’ve always been concerned with issues regarding gender and sexuality in both past and present societies. Even when we don’t realize it, how we label ourselves is a factor that greatly influences our life experiences. Growing up, I was faced with many such instances – I would be walking down a street and receive comments from men that would make me incredibly uncomfortable. No matter where I was, what I wore, or who I was with, I frequently seemed to encounter men who felt entitled to give their opinions on my body. Because of this, I decided it would be prudent to examine how violence against women has changed across decades – with a specific focus on Puerto Rican society. As I aimed to uncover the root of this problem, I will present as evidence key cases that have inspired island-wide uproar.

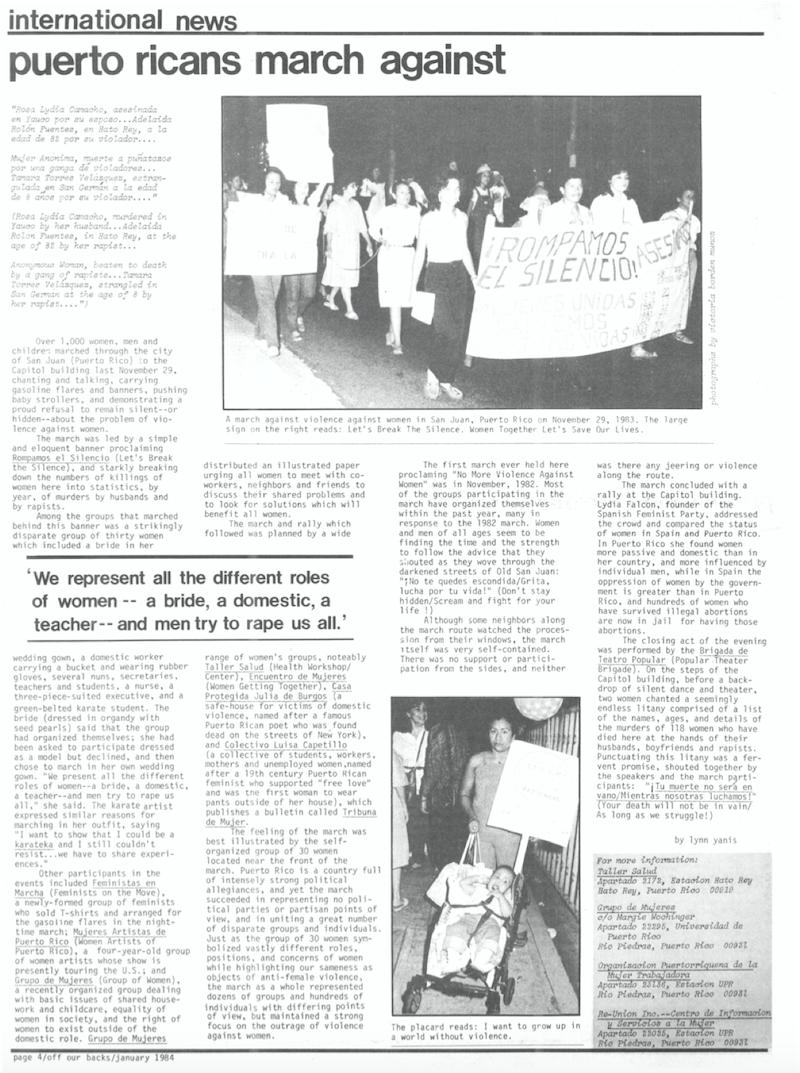

Newspaper coverage on protest

The Puerto Rican feminist movement

Domestic violence is an unforgiving global problem that affects the lives of women in Puerto Rico every day. Only recently has the issue of violence against women has been mainstreamed via agencies that address health, human rights, women’s rights, and refugee protection.

Although the vast majority of domestic abuse cases are not reported to law enforcement agencies, police statistics on the Island reveal an alarming trend. In 1983, eighty-one percent of the murders of women were committed by a family member or friend – which to sixty-four percent in 1985. This points to incidents of domestic abuse as being increasingly aggressive that would rise in both frequency and intensity.

As a result of the Puerto Rican government’s inability to ratify international human rights treaties and conventions on its own, members of the feminist movements took matters into their own hands. As can be seen, by the news article above, women from all over the Island, along with various established feminist groups, took to the streets of the Capitol to protest the dismissal of this violence pandemic. Recognized groups like the Casa Protegida Julia de Burgos (Julia Burgos Protected House) and the Colectivo Luisa Capetillo [1] could be seen at the forefront of this march.

Over the last decade, some significant progress has been made in the area of domestic violence in Latin America. Puerto Rico, through the enactment of Law 54 [2], was included as one of these Latin American nations acting to end impunity for domestic violence perpetrators (Roure, 2011).

The Casa Protegida Julia de Burgos is the first shelter for women who are survivors of domestic violence established in Puerto Rico in 1979. Since it was founded, Casa Julia has been instrumental in preparing plans for escape, security, and contingency, in creating safe spaces for mothers and their children being stalked by their aggressors or who are at imminent risk of suffering physical or psychological damage. Through shelter, orientation, and counseling, survivors are guided through an empowerment process that allows them to recognize their potential to take control of their lives and live free of violence.

You can find more information about Casa Protegida Julia de Burgos on their website www.casajulia.org. If you are in a situation of violence you can contact Casa Protegida Julia de Burgos at 787-723-3500 for help.

Machismo and violence

A culture of male dominance and patriarchy in Puerto Rico plays a major role in the underreporting of domestic violence by female victims.

“Two principal characteristics appear in the study of machismo. The first is aggressiveness. Each macho must show that he is masculine, strong, and physically powerful. Differences, verbal or physical abuse, or challenges must be met with fists or other weapons. The true macho shouldn’t be afraid of anything, and he should be capable of drinking quantities of liquor without necessarily getting drunk.

The other major characteristic of machismo is hypersexuality… the culturally preferred goal is the conquest of women, the more the better. To take advantage of a young woman sexually is cause for pride and prestige, not blame. In fact, some men will commit adultery just to prove to themselves they can do it… Sexual conquest is to satisfy male vanity. Indeed, one’s potency must be known by others, which leads to bragging and storytelling…The woman loves but the man conquers – this lack of emotion is part superiority of the male.” (Ingoldsby, 1991)

From the ‘80s to 2020: comparison of past and present crimes

“In 1995-1996, 13 percent of adult women in Puerto Rico reported that they had been physically assaulted by an intimate partner. From 1997 to 2003, women were the large majority of domestic violence victims, comprising approximately 83-90 percent of the targets in domestic violence incidents. In 2003, a woman was killed on average every 15.2 days. The data from 2001 to 2008 indicates that 178 women were killed by their partners or ex-partners on the Island.” (Roure, 2011).

In 2018, there was an increase of more than double of deaths due to gender violence in Puerto Rico compared to the previous year. The island hadn’t seen a surge in cases like this since 2011. Out of forty-four women murdered, twenty-three were at the hands of their current or ex-partners. These women were either stabbed, beaten, or shot. Some were killed in front of their young children, while others were thrown onto the road like objects that were no longer useful. All of them had their dignity, their rights, and their futures ripped away.

Jaqueline Vega Sánchez, 43 years-old

- Her body was found in a state of decomposition inside a plastic bag on the streets of Río Piedras. Blood stains were found inside the residence of her ex-husband.

Zuliani Calderón Nieves, 38 years-old

- The murderer broke the glass in the driver’s side door of her car before shooting Zuliani several times. The crime occurred in front of her two children, they were 10 and 13 at the time.

Moesha Hiraldo Maldonado, 19 years-old

- After being transported to the hospital for multiple gunshot wounds in her chest and legs, Moesha died. She was a mother of two.

Marisol Ortiz Alameda, 28 years-old

- Before committing suicide, Marisol’s boyfriend shot her multiple times. The murder occurred in Lajas.

Ilia Millán Meléndez, 44 years-old

- Five days after being reported missing in Fajardo, her body was found in a state of decomposition stabbed multiple times in a cemetery in San Lorenzo.

What now?

To truly achieve change, we need to hold accountable those in power that have turned a blind eye for far too long. There needs to be ongoing dialogue between the Puerto Rican government, the victims who manage to escape with their lives, and the community organizers to properly define the needed measures and how to properly protect its citizens.

The Women’s Advocate Office is one of those organizations already working towards eradicating gendered violence. They have developed an educational campaign that emphasizes our responsibility as citizens and victims’ protection as part of their empowerment process. One of their campaign slogans, “Love doesn’t kill, but machismo does”, looked to engage the community and educate women.[3]

It’s important to understand that no one is exempt from this pandemic. If you are interested in learning more about the effects of gendered violence in Latin America, see Repetto’s “Women against violence against women”, Hume’s “The politics of violence”, Fregosos’ “Terrorizing Women: Femicide in the Americas” and countless others.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of gendered violence, access this website for support: https://www.thehotline.org

Bibliography

Fregoso, Rosa-Linda, Cynthia Bejarano, Marcela Lagarde y de los Rios, Mercedes Olivera, and Rosa Linda Fregoso. Terrorizing Women: Feminicide in the Americas. Durham, UNITED STATES: Duke University Press, 2010. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/wfu/detail.action?docID=1171759.

Hume, Mo. The Politics of Violence: Gender, Conflict and Community in El Salvador. The Bulletin of Latin American Research Book Series.Chichester, U.K.; John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

Repetto, Lady E.. “Women against violence against women.” In Compañeras: Voices from the Latin American Women’s Movement. Edited by Gaby Keippers. Latin America Bureau; London, 1992.

Rolón, H. “Ni Una Menos | El Nuevo Día.” Las huellas, a un año de María – El Nuevo Día. Accessed November 5, 2020. https://niunamenos.elnuevodia.com/.

Roure, J. “Gender Justice in Puerto Rico: Domestic Violence, Legal Reform, and the Use of International Human Rights Principles.” Human Rights Quarterly 33, no. 3 (2011): 790–825.

Yanis, L. “Puerto Ricans March Against.” Off Our Backs 14, no. 1 (1984): 4–4.

Ingoldsby, B. “The Latin American Family: Familism vs. Machismo.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 22, no. 1 (1991): 57–62.

I am a native Puerto Rican who is passionate about shedding light on the pandemic that is gendered violence on the Island and to bring justice to its victims. As of 2020, I am in my third year at Wake Forest University, where I hope to obtain a degree in Biology so as to continue on the path to an M.D.

- Luisa Capetillo was a pioneer of feminism and unionism. She always stood out for being an active woman and for her fight for the equality of women and the rights of workers. She promoted the anarchist ideal and feminism through her writings. ↵

- Law for the Prevention and Intervention with Domestic Violence, see http://www.bvirtual.ogp.pr.gov/ogp/Bvirtual/leyesreferencia/PDF/Y%20-%20Ingl%C3%A9s/54-1989.pdf ↵

- To learn more about what the WAO does in Puerto Rico, see Roure’s Gender Justice in Puerto Rico: Domestic Violence, Legal Reform, and the Use of International Human Rights Principles. ↵