10 Sexism Takes Flight

Olivia Frank

In the 1960s and 70s, a stewardess’ ability to sell sky high sex was every airline’s top priority.[1] Sexualized stewardesses were marketed as objects for consumption, ready to serve your every need. Between sexist job requirements to skimpy uniforms, airlines did everything they could to manufacture and market the sexiest stewardess.[2] Weight, marital, and age requirements ensured that these stewardesses met Hollywood-like standards for beauty and grace.[3] Advertisements left little to the imagination marketing sexual availability as a complementary addition to your in-flight experience.[4] Finally, tight, bright miniskirts put the finishing touches on making these women the object of everyone’s desires.[5] Although being a flight attendant was a unique opportunity for women to escape the confines of the home and enter the job market, a stewardess’ physical appearance was valued much more highly than her ability to perform important in-flight tasks.[6]

To even be considered for the position, women had to meet extremely high sets of standards. Nothing was off the table. Every part of the body was subjected to scrutiny to ensure industry expectations were met. Although some characteristics like comportment and class could be taught, for many their physical appearance wouldn’t even get them through the initial interview.[7] Unsurprisingly, weight was a main focus of attention and body measurements were a required portion of the job application. In an interview, Kathleen Heenan recounts her experience as a flight attendant for Trans World Airlines during 1965-1977. Before taking flight, she remembers being subjected to routine weight checks. If a stewardess was not maintaining or losing adequate amounts of weight, she could be suspended without pay for not meeting the airline’s desired image. Due to this policy, many flight attendants resorted to diet pills and diuretics to stay employed.[8] In another interview, former Pan Am stewardess Patricia Ireland emphasizes how heavy the factors of weight and overall body type truly played in the hiring process.[9]

“One of the airlines that when they interviewed me, uh, the first thing you did when you walked in the room was get on a scale. I went to interview for another airline and I had on a skirt. It was kind of flared at the bottom, and the interviewer asked me to pull my skirt—you know, pull it back tight against my legs so he could see the lower part of my body, um, in case I was disguising thunder thighs under my flared skirt.”[10]

For airlines, what mattered the most was physical appearance. As long as her body met their desired image, they would figure out a way to prepare her for a stewardess’ actual in-flight duties.

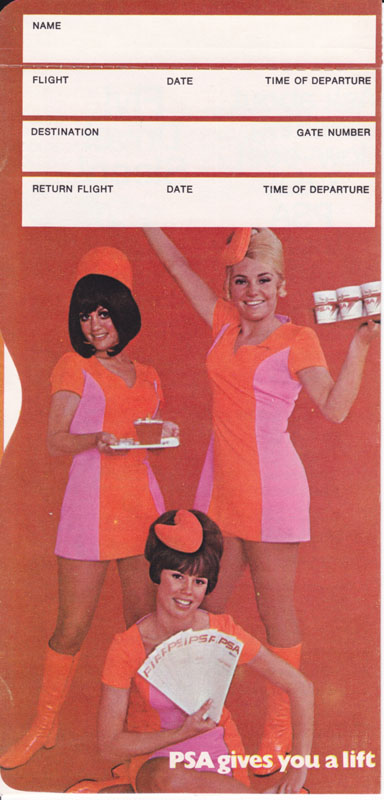

Skimpy uniforms then perpetuated this image of sexual availability. By leaving little to the imagination, tight miniskirts and go-go boots, like the ones featured above, marketed a sexually promiscuous stewardess to passengers. Bright colors were also used to sell a flight attendant’s body as a fun, luxurious object for consumption. During this time, a sexual and cultural revolution was sweeping across the country. Bright colors became a symbol for glamour and extravagance. Flight attendants soon began sporting bright shades of pinks and oranges to reflect the changing attitudes across the nation.[11] However, a stewardess’ uniform did not stop at the outerwear, many airlines required restricting girdles and bras. To ensure that a stewardess’ body was properly shaped and flaunted at all times, superiors were also allowed to visibly check and confirm that these undergarments were worn properly. Finally, to put the finishing touches on their ideal physical appearance, many airlines then strongly encouraged the use of false eyelashes and primped hairstyles.[12]

The requirements of the job were not limited to concerns about physical appearance. Stewardesses had to sign off any and all rights to pregnancy and marriage. If either of these two things occurred, they had to honor their initial agreement and resign immediately. Flight attendants also entered this market well aware that this would only be a short term job. Many airlines adopted a mandatory retirement age between 32 and 35. Once stewardesses reached their mid-thirties, they knew that they would be tossed aside and replaced with a newer, perkier version of themselves.[13]

Additionally, the slogans and images featured in airline advertisements worked together to broadcast a flight attendant’s sexual availability. In 1965, United Airlines debued the familiar slogan “Come fly the friendly skies of United” to keep up with an era defined by sexual freedom and glamour. Here, United capitalized on the objectification of women to increase revenues by inviting the consumer in to enjoy much more than just smooth, efficient flights. By promoting a caring, personal side to the company, United also implies that these stewardesses were there to serve your every need.[14] Other advertisements from United promoted similar agendas. In 1967, they ran an ad campaign promising that “We go all out to please you!”[15] During this year, they also redesigned company uniforms to properly flaunt their stewardesses. A wave of miniskirts and A-line dresses, like the ones below, took the company by storm.[16]

Among passengers, it became a common belief that when you purchased an airline ticket, you also purchased the right to consume these women. The combination of sexualized advertisements, skimpy uniforms, and high beauty standards made her an object for the male and female gaze alike. She was the object of everyone’s desires. If you didn’t want to get with her, you wanted to be her.[17] Testimonies from former flight attendants reveal the true extent to which airlines promised the stewardess’ body a part of the in-flight experience. In an interview concerning her time as a flight attendant in the early 1970s, Paula Kane remembers feeling like “…because I had a uniform on, I was somehow public property.”[18] Everyone from passengers to pilots felt entitled to consume these women.

This was not an uncommon feeling among stewardesses. When describing her experience, Cindy Hounsell remembers feeling like Pan American World Airways had promised customers that she would fulfill their every desire, no matter if this was related to sex or safety. “The minute you said you were a stewardess or a flight attendant, it was like there was this presumption that you were readily sexually available.”[19] Whether on the jetway or at home, once a woman was viewed as a flight attendant, it was almost as if they were no longer entitled to their bodies.

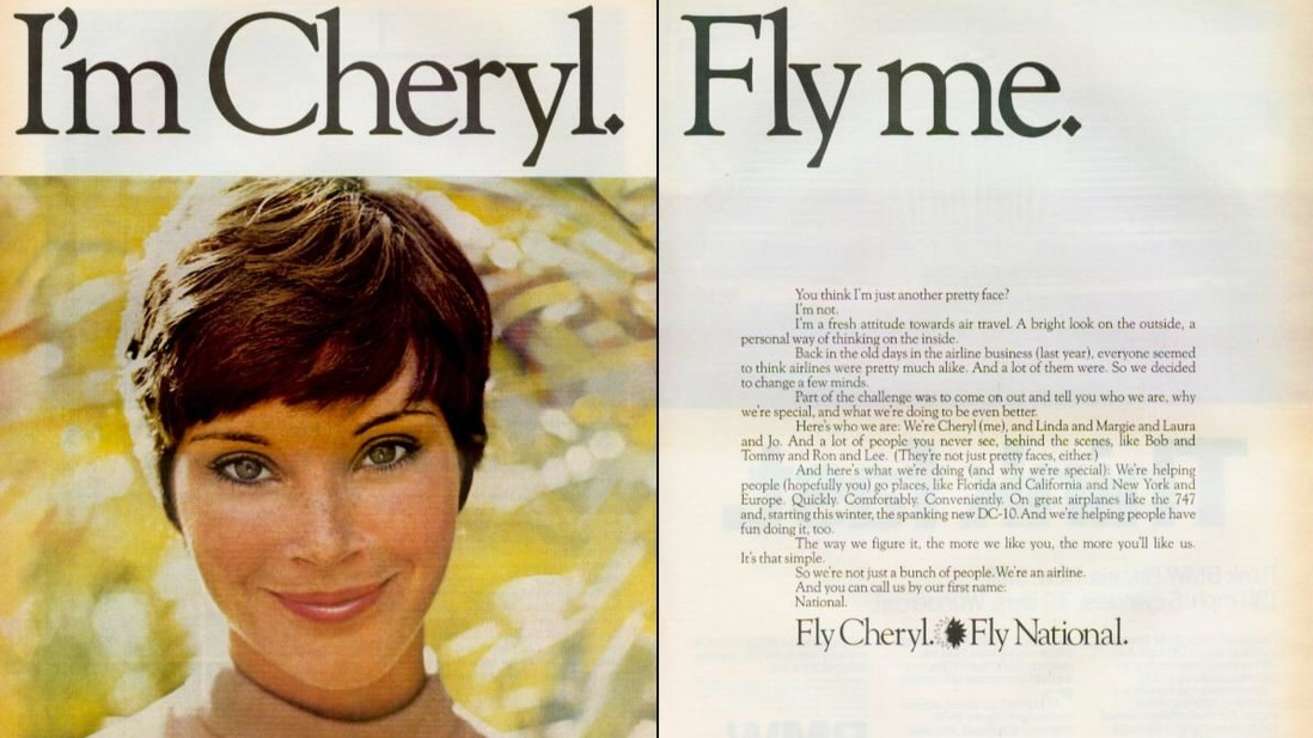

Over time, these problematic industry standards were slowly rescinded. By the mid 1970s, all US airlines had removed bans on pregnancy and mandatory retirement ages. The revoking of these policies also allowed the role of a flight attendant to become a long-term, profitable career for many women. However, it was not as if everything immediately got better for these stewardesses. Many sexist policies stayed in place throughout the 1970s. Flight attendants were still subject to strict weight requirements. Restricting girdles also remained part of a stewardess’ uniform.[20] Beyond this, sexist advertisements continued to be broadcasted across the country. In 1971, National Airlines ran a series of “Fly Me” campaigns including the one featured above. Taglines like “Hi, I’m Cheryl and I’m going to fly you like you’ve never been flown before” left little room for interpretation amongst customers. Flight attendants were marketed as objects for consumption. This advertising campaign, packed with sexual innuendos, made sure the customer knew these stewardesses would get you where you wanted to go. “Fly Me” advertisements remained in flight and circulated across the country for the next five years.[21] Other airlines had similar aspirations of selling jet sex. In 1971, Pacific Southwest Airlines promoted “giving you a lift” (shown below), ensuring that a passenger’s every need would be met.[22]

Eventually, female stewardesses were able to find their voices once and for all. In 1972, a new feminist group entitled Stewardesses for Women’s Rights took the first step in empowering stewardesses to stand up and fight the sexism and discrimination dominating the industry. Around the same time, males were also beginning to be allowed into the industry. Not only were stewardesses now backed by the voices of many, but they were also armed with the fight for equal rights amongst genders. Without this newfound confidence and power, expectations for female flight attendants would have never changed.[23]

Up until the early 1970s, a flight attendant’s skirt kept getting progressively shorter. In 1974, males were used as leverage to finally ditch the miniskirt once and for all and usher in a new wave of professional attire. Many other policies followed a similar trend. The requirement of nail polish, for instance, was revoked because airlines could not apply this rule to both genders. The largest abolition came with the girdle requirement. Stewardesses cleverly demanded that the men also be required to wear jockstraps, putting the airlines in a lose-lose situation and forcing them to get rid of this sexist policy. In the 1980s, stewardesses finally won the fight against workspace objectification when the lingering pregnancy and weight requirements were revoked at last.[24] One thing is for certain, until the sexualized advertisements, skimpy uniforms, and high beauty standards were finally off the table, the main purpose of a stewardess was to be a sexual object for consumption.

For more images of flight attendants during the 1960s and 1970s, see San Diego Air and Space Museum Archive on Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/search/?user_id=49487266%40N07&view_all=1&tags=stewardess

Olivia Frank is a Sophomore at Wake Forest University.

- Philip James Tiemeyer, "Stewards and the Vestiges of Sexism," in Plane Queer: Labor, Sexuality, and AIDS in the History of Male Flight Attendants (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 135-138. ↵

- Peter Lyths, "'Think of Her as Your Mother,'" The Journal of Transport History 30, no. 1 (June 2009): 11-12, https://doi.org/10.7227/TJTH.30.1.3. ↵

- Allison Vandenberg, "Toward a Phenomenological Analysis of Historicized Beauty Practices," Women's Studies Quarterly 46, no. 1/2 (Spring/Summer 2018): 176-177, JSTOR. ↵

- Sexing History, season 1, episode 6, "Sexism Takes Flight," hosted by Gillian Frank and Lauren Gutterman. ↵

- Vicki Vantoch, "From Warm-Hearted Hostesses to In-Flight Strippers," in The Jet Sex: Airline Stewardesses and the Making of an American Icon (Philadelphia, Penn.: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 166-168. ↵

- Vandenberg, "Toward a Phenomenological," 176. ↵

- Vandenberg, "Toward a Phenomenological," 176-177. ↵

- Sexing History, "Sexism Takes." ↵

- Sexing History, "Sexism Takes." ↵

- Sexing History, "Sexism Takes." ↵

- Vantoch, "From Warm-Hearted," 153-185. ↵

- Sexing History, "Sexism Takes." ↵

- Sexing History, "Sexism Takes. ↵

- Vantoch, "From Warm-Hearted," 171-173. ↵

- Vantoch, "From Warm-Hearted," 178. ↵

- Vantoch, "From Warm-Hearted," 177-178. ↵

- Vantoch, "From Warm-Hearted," 153-185. ↵

- Sexing History, "Sexism Takes." ↵

- Sexing History, "Sexism Takes." ↵

- Tiemeyer, "Stewards and the Vestiges," 135-138. ↵

- Lyths, "'Think of Her as Your," 11-12. ↵

- Lyths, "'Think of Her as Your," 11-12. ↵

- Tiemeyer, "Stewards and the Vestiges," 135-138. ↵

- Tiemeyer, "Stewards and the Vestiges," 135-138. ↵