17 Natal Organization of Women and their Fight for Equality in Apartheid South Africa

Michaela Barrett

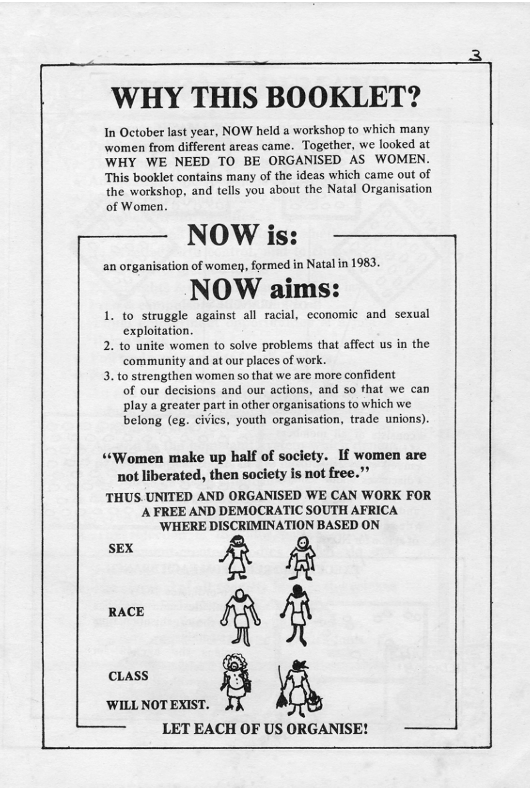

The flyer above, was published in 1985 by the Natal Organization of Women (NOW). The Natal Organization of Women was founded in 1983, in Durban, South Africa.[1]

The primary source highlights the groups aims, as well as who they appealed to and the demographics that they were comprised of. While NOW was a women’s group, and fought for the rights and equality of women, they also fought for political reform of the apartheid regime.[2]

Also, Apartheid was in place in South Africa from 1948 until the 1990s. It was a system of institutionalized segregation on the grounds of race. Many complex laws were instituted by the government to keep non-whites separate. Inter-racial sex and relationships were punishable by law. Non-whites had dedicated land areas dedicated to their specific race where they were allowed to live, this was known as the Land Act. Women’s organizations that had a political agenda appealed to females at the time because they felt that they were often ignored at organizations where men where present, such as groups fighting primarily for racial justice.[3]

Women’s organizations in South Africa felt that they should be inclusive of all races to diversify their reach.[4] However, NOW was the only group like this, that worked across race, in Natal at the time.[5] This was particularly important during apartheid because it promoted unity and gave strength to the oppressed classes and races.[6] However, it also complicated logistics and meetings. With pass laws and travel routes intended for getting poor black and colored individuals merely to and from work, it was impossible to find a place to hold meetings that everyone could attend.[7]

NOW affiliated with the United Democratic Front (UDF), a political party that stood in opposition to apartheid and the governments proposed constitutional reforms.[8] NOW originally affiliated with the UDF in order to merge their demands as women with their demands against apartheid.[9] They felt that it was a development that made sense because it linked women’s struggles to struggles for democracy, and women’s rights were intrinsically linked to the struggle for democracy.[10] However, it was a controversial affiliation because it caused a shift away from the associated women deciding what they felt necessary to advocate for, towards merely becoming the voice of women for the UDF.[11]

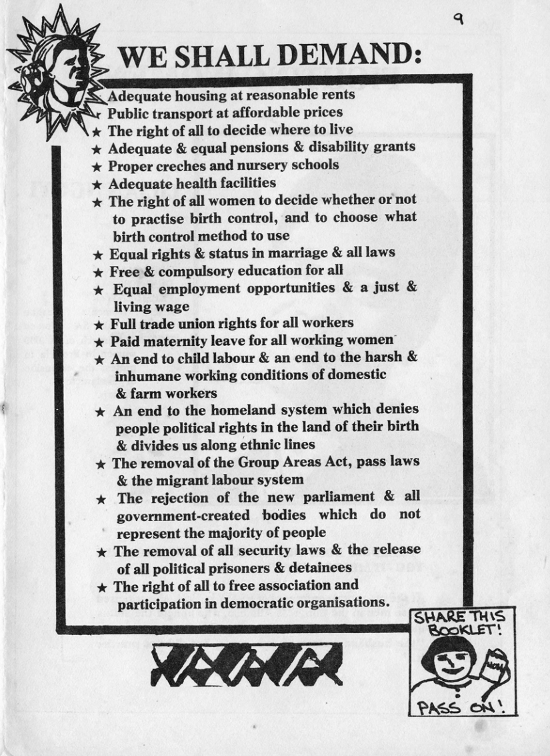

NOW fought across the racial divide against the lack of maternity benefits and childcare, as well as for equal work opportunities.[12] There seemed to be an institutional oppression of women; they were narrowed into traditionally female oriented jobs, it was not required that women be paid the same as men for the traditionally unfemale jobs that they could get, and taxes were imposed on women that brought an income back to her family if she was married – penalizing her for contributing to her family.[13] In terms of their struggle against apartheid, NOW fought against pass laws and the Group Areas Act, the high cost of living, the creation of the tri-chimeral parliament, and adequate healthcare facilities.[14] These demands show that while NOW was focused on Women’s Rights, they were very much placed in the context of apartheid, and the unique struggles faced by women during that regime. While women were fighting for their rights and freedoms, they were also fighting politically for human rights.

The women in these organizations believed that a struggle for national liberation, and a struggle for women’s rights should, nor could, be dealt with separately.[15] Women involved in these organizations, such as NOW, faced harassment and violence from men that did not support their aims. Women were murdered, raped, detained and tortured. Often, effort was not even made to investigate those cases, thus many perpetrators were not prosecuted.[16] Women in these groups were willing to jeopardize their safety to fight for what they believed in.

Overall, analyzing NOW as a women’s organization highlights the complexities of apartheid. Women felt they were not heard in organizations where men were present, and they felt they had a responsibility to take action for the changes they wanted to see. While they faced challenges, they worked against all odds to get their message heard.

Michaela is a sophomore majoring in English and double minoring in Psychology and Journalism. They are originally from Cape Town, South Africa. Their hobbies include photography and hiking. They are an avid reader.

- Amandla Durban, “The Natal Organisation of Women,” AMANDLA! (blog), August 9, 2018, https://amandladurban.org.za/the-natal-organisation-of-women/. ↵

- Shireen Hassim, Women’s Organizations and Democracy in South Africa: Contesting Authority (Madison, United States: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006), http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/wfu/detail.action?docID=3444769. 48. ↵

- Hassim. 56. ↵

- Hassim. 78. ↵

- Hassim. 79. ↵

- There were four main racial groups as defined by the law under Apartheid. These were, white, Asian/Indian, Black or Bantu, and colored. The level of oppression applied to each race followed the same order. Whites were the favored race, and Asians and Indians were treated more lightly than blacks and coloreds. While there was no legal oppression in place on white English-speaking citizens, they were typically considered to be slightly more lowly by the white Afrikaaners. The terms white, Indian/Asian, and colored are still the same today in the desegregated South Africa, but “Bantus” are only called black today. Colored is the term used to refer to mixed race individuals in South Africa, and is still considered to be politically correct there. ↵

- Hassim, Women’s Organizations and Democracy in South Africa. 78. On Pass Laws, they required black and colored South Africans over 16 years old to have with them at all times what was essentially a passport – referred to as a passbook, or “dompas” in Afrikaans. These passbooks contained the individual’s photograph, their fingerprints, employment details included where they were permitted by law to work, and government permission to be in certain areas of the country. Police could render one ineligible to work or preside in a certain area at any time with no explanation. If an individual was without their passbook at any time for any reason – having had it stolen, misplacing it, or forgetting to carry it – they could be arrested and imprisoned. See “Apartheid Legislation,” accessed November 11, 2020, http://www.cortland.edu/cgis/suzman/apartheid.html. ↵

- Hassim, Women’s Organizations and Democracy in South Africa. 48. ↵

- Hassim. 265. ↵

- Hassim. 69. ↵

- Hassim. 69. ↵

- “NOW-2.Png.Jpg (912×632),” accessed November 2, 2020, https://i0.wp.com/amandladurban.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/NOW-2.png.jpg?ssl=1. ↵

- Eleanor M. Lemmer, “Invisible Barriers: Attitudes toward Women in South Africa,” South African Journal of Sociology 20, no. 1 (1989): 30–37, https://doi.org/10.1080/02580144.1989.10432899. ↵

- “Organizing Women Now by Natal Organisation of Women, 1985 | South African History Online,” accessed October 20, 2020, https://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/organizing-women-now-natal-organisation-women-1985. ↵

- Nozizwe Madlala-Routledge, “What Price for Freedom? Testimony and the Natal Organisation of Women,” Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity, no. 34 (1997): 62–70, https://doi.org/10.2307/4066243. 67. ↵

- Madlala-Routledge. 63. ↵