9 Women in Maoist Propaganda: An Overview of Femininity as State Apparatus

Stevie L.

In Ideology and Ideological State Apparatus (Notes Towards an Investigation) (French: Idéologie et appareils idéologiques d’État (Notes pour une recherche)), Louis Althusser,[1] a renowned Marxist philosopher, proposes that the ruling class employs the repressive state apparatuses (RSA) as a tool to subjugate the working class; the social functions of RSA include government, courts, police, military, etc. and serve to repress the social classes on demand via violent and/or nonviolent methods.[2] Althusser further distinguishes repressive state apparatuses between ideological state apparatuses (ISA), which are social institutions and entities that propagandize ideologies in favor of the ruling class. Such apparatuses include the educational institutes, churches, family, social clubs, etc.[3]

Althusser further theorizes that ISA use physical nonviolence to achieve the same goals as RSA in institutions that are ostensibly apolitical, rather than being formally a part of the state as RSA are. ISA propagates ideologies, rather than expressing and imposing violence or the threats thereof, that strengthen the dominance and control of the ruling class. In attribution to psychosocial theories, it is contended that those who are subject to ISA are coopted in fear of social rejection, ostracization, isolation, and ridicule.

In this essay, the ideological state apparatuses are contextually examined in the visual media of propaganda posters from 1950s and 1960s communist China encompassing images of women and other representations of femininity, whereby arguing that such images are epitomic of the pervasive—as well as intrusive—applications of ideological suppressive apparatuses. The will of the state is thereby imposed upon men and women, in accordance with the will of the state and its specific political agendas, via establishing and normalizing the standards of socioculturally acceptable femininity and womanhood. In other words, the states exploit its power over the media and manipulate what is wanted to “be a woman,” so as to achieve its political purposes and to maintain desired social orders.

After the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) prevailed in the Chinese Civil War over the Kuomingtang (“The National Party”/KMT) in 1949, the state-led movement called Women’s Liberation. During this period a variety of policies had been experimented with and codified. The very first law passed in People’s Republic of China (PRC) was in fact a marriage civil law enacted on May 1, 1950. The New Marriage Law was a radical divergence from the existing patriarchal traditions and statutory practices. Traditionally, Chinese marriage often took place through arrangement or coercion; women were not allowed to seek nor initiate a divorce, while concubinage was a commonplace. The new law explicitly banned bigomy/polygamy, concubinage, and marriage by proxy and prioritized the consent from both the man and the woman upon marriage registry.[4]

Old-fashioned aesthetic ideas on women, however, were tenacious. Therefore, it is of vital importance to see what women in the past were presented so that one understands how CCP-revolutionaries envisioned women’s role in the nascent (ideally) socialist economy in contrast with its capitalistic counterpart that the CCP had just upended. By the early 20th century, the visual tradition that establishes women as objects for male consumption via male gaze had been established. Advertisers, one that went extinct later due to the communist revolution which ceased market economy in China, featured young, attractive women in the tantalizing—yet still considered modest in accordance with the Confucian traditions—dress Cheongsam, a new sartorial invention that draws attention to the wearer’s voluptuous physique and caters to a specifically Chinese sense of aesthetics. Much of the advertising was ubiquitous in port cities like Shanghai or Tsingtao—forefronts of China’s first engagement with the globalized economy—where imported products gained much popularity.

However, artists having been known for their work of beautiful women, ironically, shifted gears after Mao’s ascension to power in fear of their old stylistic choices were representative of their “petit-bourgeois-class aesthetics,” which could be used against them as evidence of their political disloyalty. Artists, such as Jin Meisheng, positioned their artistic thematic foci later in political adulation as well as dissemination of state policies. The artists strive to construct images of women that nonetheless pertains to the traditional beauty standards of women that exemplify demureness, elegance, and modesty.

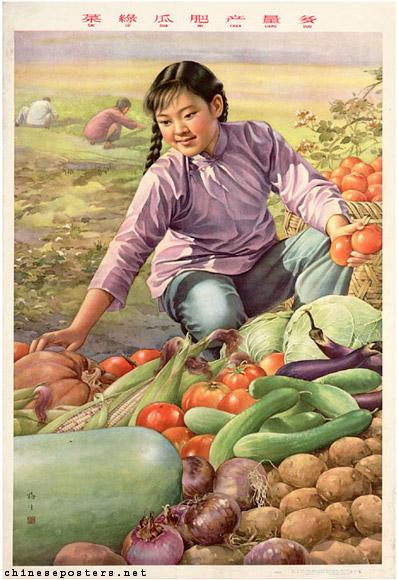

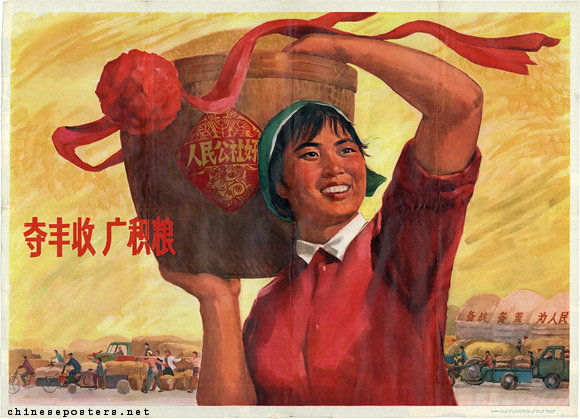

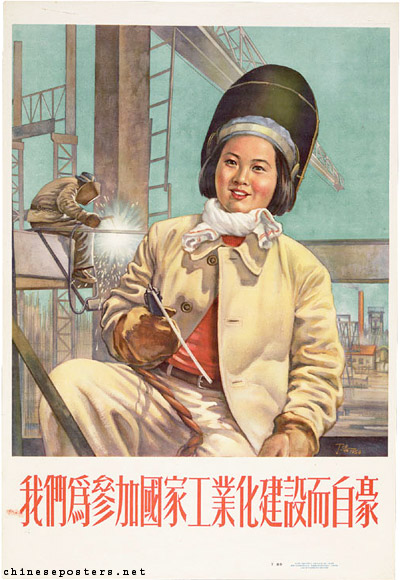

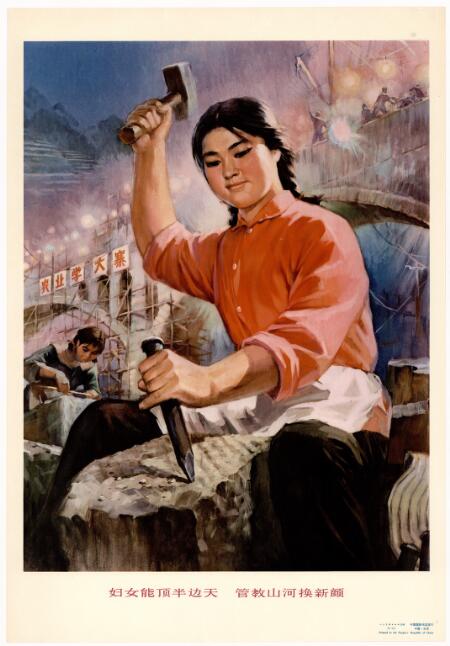

Despite such consistency in objectifying approaches to depict women, the new genre of art on propaganda posters in general endeavors to convey the emancipatory message of women. An overarching element in poster art in this period is female professionals, many in uniforms, participating in a wide range of activities agriculture, industry, scientific studies, etc. Therefore, for good reasons, the CCP has been active in lauding itself as the champion of women’s liberation. Mao Zedong’s famous dictum, “Women hold up half of the sky,”[5] (later becoming a cultural sensation and icon within the progressive left in the West) explicitly urges women to consciously and actively engage in the great endeavor of reconstructing the socialist China. Therefore, women in these images are often shown to be somewhat muscular—and even masculine—so as to justify the political proposition that women are just as valued, if not more, in professions that entail much physical labor. The following poster showcases a woman in “The Great Leap Forward.”

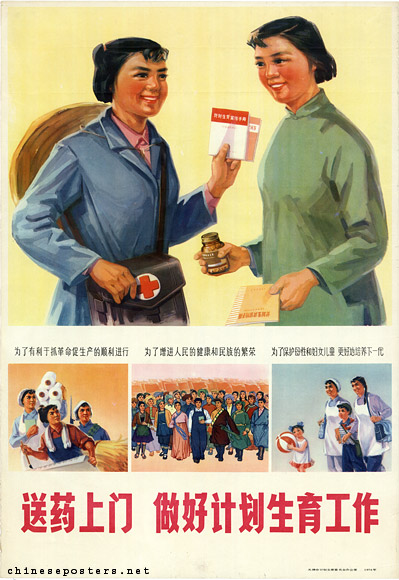

It is worth mentioning that, however, these representations of women in no ways mean the absence of traditional roles of women as caregiving, child-rearing nurturers in the State narrative. In the first few years Mao held the conviction that the larger the population, the greater the industrialization force. Soviet-style policies were implemented to encourage reproduction; awards such as “Model Mother” and “Hero Mother” were granted to women who gave birth to, respectively, five and ten children. The policy later made the drastic change into the infamous “Family Planning” policy and added to the Chinese constitution as a basic state policy, which restricted most Chinese households to have one (in a few cases, two) child(ren). The evolution of the propaganda posters records exactly how the state exercises its—first advisory and then complete controlling—influences on Women’s bodies. The first two of the following posters, albeit not explicitly encouraging pregnancy, nonetheless suggests that a household of three or four kids are to be aspired; while later propaganda for Family Planning policies explicitly addresses women’s pregnancy: that women shall follow the rules of the country.

These propaganda posters provide a unique perspective on how the ideological state apparatus come in effect via the visual avenue that no one in Maoist China was exempt from; they also serve as an example of how ideological state apparatuses often intersect and act in synergy with one another. These propaganda posters instill the people with the state-approved ideas on what socially acceptable womanhood is: one that is conscious and grateful for CCP’s emancipation, one that actively contributes to the state and its lofty feat, one that is no longer bound by the outdated expectation of subjugate to patriarchal marriage system, yet is still expected to be ready to go back to the childrearing roles should so the state wishes—to any extent as the state wishes. These propaganda posters unveil the complex dynamics between the deeply ingrained ideas on women, and the communist dictatorship that strives to redefine womanhood and femininity, the dynamics that are still present today, as China faces an aging population and the emerging middle class undergoing unprecedented liberalization.

Stevie L. is a student of Wake Forest University, Class of 2022. He is an aspiring mathematician, a language enthusiast, and a NCAA fan. He thinks hot dog is just underdressed sandwich.

- Louis Althusser (1970). Idéologie et appareils idéologiques d'État (Notes pour une recherche), 151. ↵

- Vincent B. Leitch (2001). The Norton Anthropology of Theory and Criticism. 1491-1492. ↵

- Leitch, 1488-1491. ↵

- Chen, Xinxin (March 2001). "Marriage Law Revisions Reflect Social Progress in China". China Today. ↵

- Perry Link notes that, in An Anatomy of Chinese, Rhythm, Metaphor, Politics by Perry Link, the Mao is quoted to have said, literally, that “women can hold up half of the sky,” not that they in fact do hold up, as indicated by “neng” in Chinese. The quote’s original date is claimed by Link to be “apparently in 1968,” albeit any contemporary source has been found. The original text is 婦女能頂半邊天, or funü neng ding banbiantian. ↵