4 Dr. Mary Walker: A Pantsuit Legend of the Civil War

Lily Silverman and Caroline DeBloom

Introduction

In 1832 in the town of Oswego, NY, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker was born[1]. The daughter of a doctor, Walker knew from an early age what she wanted to be when she grew up. At just twenty-four years old, Walker received her M.D. from Syracuse Medical College in upstate New York. Just five years later, the Civil War began. Having deep rooted loyalties to the Union, Walker decided to volunteer as a doctor in Washington D.C. where she assumed her services would be greatly welcomed and appreciated[2]. To her surprise, despite her various assets, those in positions of power often failed to see past her gender. Consequently, she was denied a commission and told she was only allowed to be a nurse. Walker was continuously denied employment as a Union army doctor, despite her several years of medical practice prior to the start of the war. As a result of these challenges as well as her upright character, Walker instead volunteered her time and skills to the Union for two years with no pay[3]. Finally, in 1864, Walker became a commissioned surgeon for the 52nd Ohio Regiment[4].

Analysis

This reality was not faced only by Dr. Walker; as you may have guessed, 19th century America was not known for its superb gender equity. Although the total U.S. population in 1860 was almost evenly split between male and female[5], women only represented approximately 300 (1.6%) of the 18,300 total degreed doctors in 1858[6], showing the true imbalances in the opportunities that existed between the sexes, in addition to the expectational differences for men and women’s occupations. Not only was the representation of women in the medical field disappointing, as was the public opinion of the existence of female doctors. A statement by Captain Ross, a soldier who (actually) respected and worked closely with Dr. Walker wrote, “‘popular opinion everywhere and the customs of our country are against the advancement and usefulness of the fairer sex’ in spite of the fact that their capabilities were unlimited”[7].

Unsurprisingly, the Union was not the only region of the country that oppressed women, the Confederacy did their fair share as well! In fact, many of the Georgians that Dr. Walker treated during the war had never encountered a female doctor[8]. Though, more and more Georgians began recognizing Dr. Walker for both her femininity and lack thereof. She had become the token female doctor, but also challenged the boundaries of gender expression— another unheard-of phenomenon in 19th century Georgia. In fact, when Walker began conjuring fears of being taken as a prisoner of war by the Confederates, she would disguise herself by wearing a dress, as no one would recognize her if she wasn’t wearing her infamous pants and jacket. An unfortunate consequence of this disguise, though, was a new fear— not of being taken as POW[9] and potentially murdered, but of sexual assault[10] . Unfortunately, these fears that women faced have not become any less inherent through the last two centuries.

So, what differentiated Dr. Mary Walker from other women working during the war? Was it just her role as a surgeon? Her skill? Dr. Walker was not only an outstanding woman by virtue of her occupation and persistence, but by the way she committed herself to challenge every sect of 19th century gender conformity. Women did, in fact, inhabit the roles of nurses and aids in the war efforts. Although this may seem like social progress— allowing women in the medical field during wartime— their roles were accepted by society because they were societally-deemed feminine. These women not only assumed “inferior” roles to men but maintained their traditional femininity and upheld every other aspect of womanhood, i.e., they did not attempt to be equal to men. Dr. Mary Walker was the exception, and thus, why she faced the scrutiny that she did. She did not just implement her talents in a men’s sphere; she had autonomy and a voice— two things most 19th century men despised for a woman to possess. While performing the same job as the men around her, Walker knew her value and demanded it be recognized[11]. In response, Dr. Cooper, a fellow member of the Union medical force, wrote to the surgeon general that Dr. Walker was “useless, ignorant, trifling, and a consummate bore,” in an effort to have her wartime contract revoked[12]. As examined, her occupation was only one element of her being that the public disapproved of; her radical choice of dress served as a chief determinant of her public image.

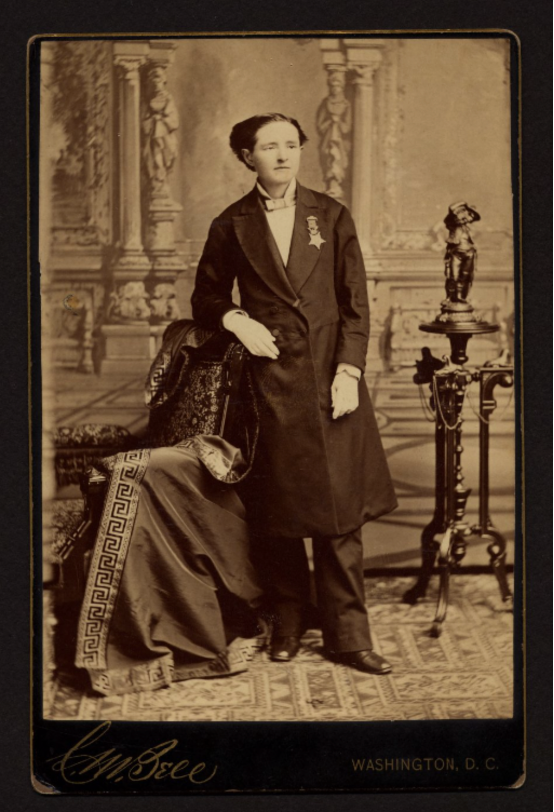

The doctress’ daily uniform did not vary much from that exhibited in the photograph above. Her loose-fitting pants and jacket were key features of her Civil War attire[13], and she often wore her hair braided back tightly behind her head[14]— at times, even covered by a top hat[15]. Later in this piece, we will discuss the significance of this attire in the context of 19th century women’s fashion.

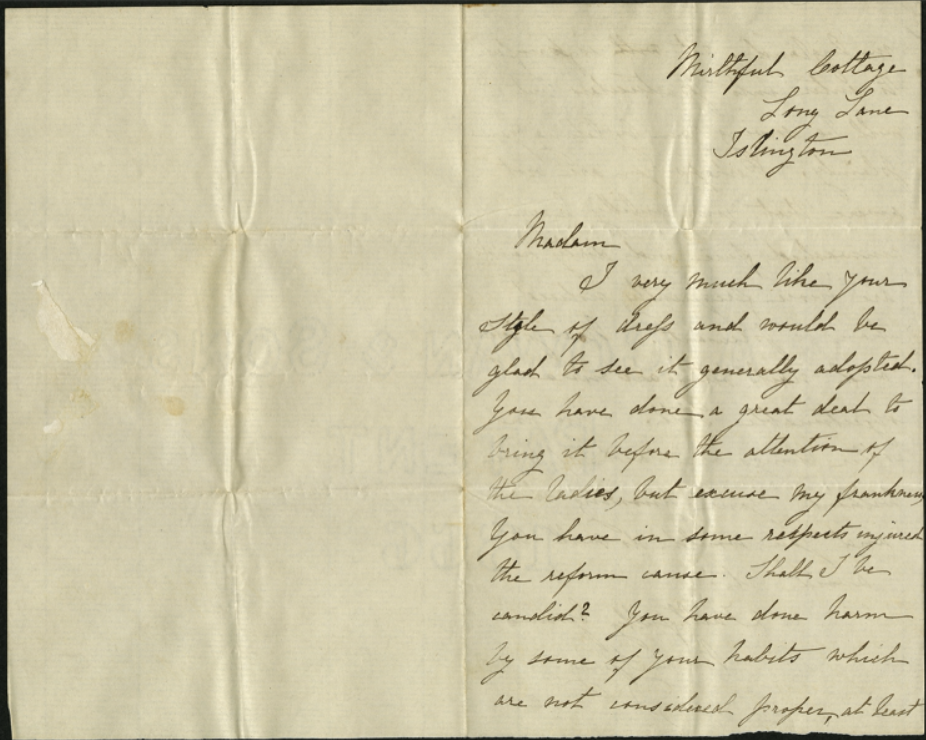

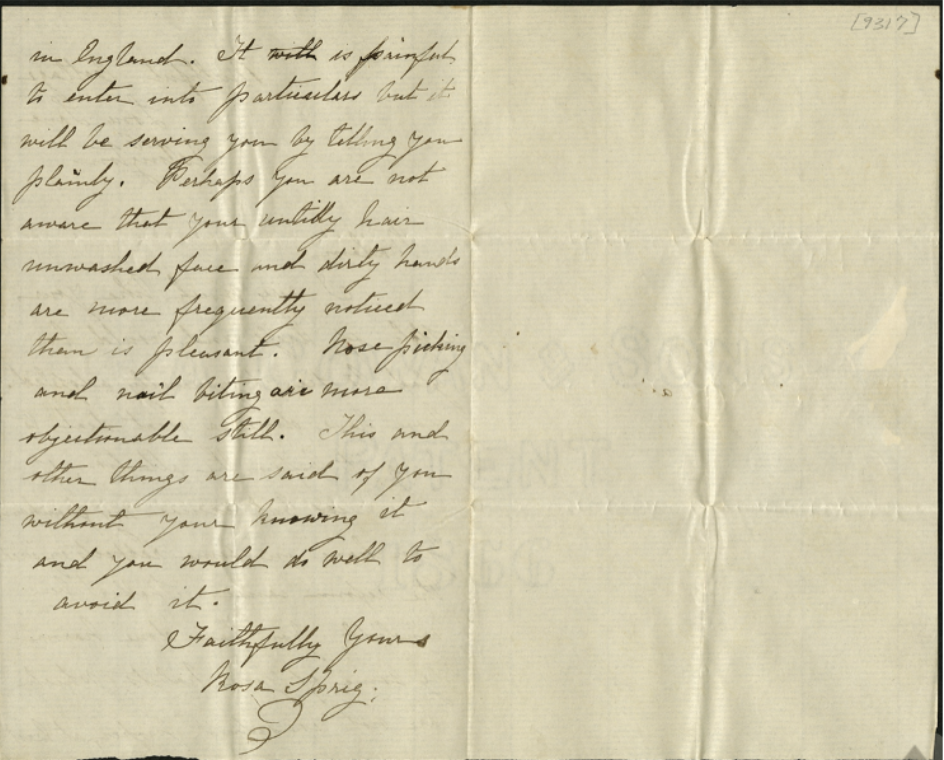

Because of these attributes, Walker encountered intense backlash from her male colleagues and even occasionally from her female admirers. One example of this came from admirer Rosa Sprig. The document pictured below is a letter written to Dr. Mary Walker from admirer Sprig:

Transcription of Letter:

“Madam, I very much like your style of dress and would be glad to see it generally adopted. You have done a great deal to bring it before the attention of the ladies, but excuse my frankness – you have in some respects injured the reform cause. Shall I be candid? You have done harm by some of your habits which are not considered proper, at least in England. It is painful to enter into particulars but it will be serving you by telling you plainly. Perhaps you are not aware that your untidy hair, unwashed face, and dirty hands are more frequently noticed than is pleasant. Nose picking and nail biting are more objectionable still. This and other things are said of you without your knowing it and you would do well to avoid it. Faithfully yours, Rosa Sprig”[16]

The letter talks about how she admires the way Walker dresses because it is different from the typical dresses and skirts. However, the letter then goes on to warn Walker to start cleaning up her act a bit so that people will take her idea of dress reform more seriously. She goes on to make note of Walker’s “untidy hair, unwashed face, and dirty hands” and her habits of “nose picking and nail biting”. Sprig was a strong admirer of Walker’s dress reform ideas but worried that if Walker didn’t appear more tidy and feminine, people would not take her ideas seriously [17].

Even before her time as a doctor and in the Civil War, Walker had always been a reformer in women’s clothing. From a young age she was taught the importance of education, literature, and finances. Aware of the fact that proper women’s clothing was more expensive than it should be, the idea of dress reform had been in the back of her mind for many years. Throughout her life, Walker would rarely wear dresses or any type of constrictive clothing because of mobility and health reasons[18]. During her time as a surgeon in the Civil War, Walker would typically wear bloomers (a type of pants) versus the typical dress that women were expected to wear[19]. As a surgeon, pants were obviously the easiest and most practical item of clothing for her to be wearing while running around trying to save peoples’ lives. But even with her profession, she was still expected to wear a dress. As mentioned in Rosa’s letter to Walker, she was also advised to keep her hair tidier, wash herself more, and simply make herself look more presentable overall. Similar to the point made about the bloomers, these seemingly ‘necessary’ feminine tasks were simply impossible to accomplish with her profession and absurd that they were considered necessary in order to be a woman.

For Walker, “dress reform was the link between her love of medicine and her belief in women’s equality”[20]. After the War ended, Walker continued to wear ‘men’s’ clothes. She was often found wearing trousers and jackets, top hats, and even cut her hair short[21]. Walker had always been involved in women’s dress reform, but after the war, she became even more invested in women’s rights movements. She frequently participated in marches and delivered speeches for legislation relating to women’s suffrage. It is even recorded that Walker was the first woman to ever try to vote in New York[22]. In her later years, she became the president of the National Dress Reform Association[23]. Similar to Walker’s discovery, many women found that wearing pants was extremely more practical than the typical dress. Reporters started bashing their new fashion choice in the press, but reformer Amelia Jenkins Bloomer fired back by writing articles about the dangers of wearing and working in conventional clothing. From then on, the new female attire was referred to as the Bloomer dress. As time went on, more and more women began joining and supporting the reform, and eventually, an editorial called The Sibyl was published. This work was dedicated to dress reform, abolition, and other women’s rights. Although some did not take it seriously, this editorial was a major step in the right direction for women’s rights and dress reform[24]. As years went on, many women stopped wearing the bloomer outfit as they thought it took away from other important women rights (education, voting, property) however Walker never stopped. By the 1870s, Walker stopped wearing dresses all together and continued to receive more and more ridicule, as well as writing two books about the dangers of women’s dresses and corsets. As the years went by, Walker found it hard to make money and moved back to her family’s farm, but never stopped fighting for women all around[25]

In short, Dr. Mary Walker’s exceptionality was not solely a result of intelligence in the medical field or the fact that she rejected traditional womens’ clothing; it was the cumulative consequence of her attack on gender conformity from all angles and every facet of her life that made Dr. Mary a truly outstanding woman[26].

Lily Silverman is a second year student at Wake Forest University with a major in biology and intended minor in economics.

Caroline DeBloom is a second year student at Wake Forest University with an intended major in health and exercise science and a minor in biology.

- “A Female Civil War Surgeon: ‘How Dr. Mary Is Remarkable.’” Doctor or Doctress? Drexel University. Accessed November 10, 2020. http://doctordoctress.org/islandora/object/islandora:1494. ↵

- BiblioBoard. (n.d.). Retrieved November 4, 2020, from https://library.biblioboard.com/viewer/1e9172f6-3fa0-4cf4-8cd4-56217c492c17 ↵

- Eggleston, Larry. Women in the Civil War: Extraordinary Stories of Soldiers, Spies, Nurses, Doctors, Crusaders, and Others. Women in the Civil War. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Incorporated Publishers, 2009. (Ch. 41) ↵

- “A Female Civil War Surgeon: ‘How Dr. Mary Is Remarkable.’” ↵

- Aaron O'Neill. Population of the US in 1860, by Race and Gender (Statista, 12 July 2019), www.statista.com/statistics/1010196/population-us-1860-race-and-gender/. (Accessed October 15, 2020) ↵

- Eggleston, Larry. Women in the Civil War: Extraordinary Stories of Soldiers, Spies, Nurses, Doctors, Crusaders, and Others. Women in the Civil War. (Ch. 41) ↵

- Harris, Sharon M. Dr. Mary Walker: an American Radical, 1832-1919 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2009.) (Pg. 54) ↵

- Harris, Sharon M. Dr. Mary Walker: an American Radical, 1832-1919 (Pg. 56) ↵

- POW: Prisoner of War ↵

- Harris, Sharon M. Dr. Mary Walker: an American Radical, 1832-1919 (Pg. 56- 57) ↵

- Clinton, Catherine, and Silber, Nina, eds. Battle Scars: Gender and Sexuality in the American Civil War. Cary: Oxford University Press USA - OSO, 2006. ProQuest Ebook Central. (Accessed October 15, 2020). (Pg. 107-109) ↵

- Eggleston, Larry. Women in the Civil War: Extraordinary Stories of Soldiers, Spies, Nurses, Doctors, Crusaders, and Others. Women in the Civil War. (Pg. 57) ↵

- Drexel University Legacy Center, A Female Civil War Surgeon: "How Dr. Mary is Remarkable” ↵

- Harris, Sharon M. Dr. Mary Walker: an American Radical, 1832-1919 (Pg. 56) ↵

- Drexel University Legacy Center, A Female Civil War Surgeon: "How Dr. Mary is Remarkable” ↵

- Rosa Sprig. “Letter to Dr. Mary Walker from Rosa Sprig,” Correspondence, 1870. From Drexel University College of Medicine Archives & Special Collections, http://lcdc.library.drexel.edu/islandora/object/islandora:1494 (accessed October 22, 2020) ↵

- “A Female Civil War Surgeon: ‘How Dr. Mary Is Remarkable.’” Doctor or Doctress? Drexel University. ↵

- Mary Walker Stood Tall For Civil War Wounded Dare: Her battlefield courage led to the Medal of Honor - ProQuest . Mink, Michael.Investor's Business Daily; Los Angeles [Los Angeles] 22 May 2013: A03. Retrieved November 4, 2020, from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1353401867?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo ↵

- “A Female Civil War Surgeon: ‘How Dr. Mary Is Remarkable.’” Doctor or Doctress? Drexel University. ↵

- Mary Walker Stood Tall For Civil War Wounded Dare: Her battlefield courage led to the Medal of Honor - ProQuest . Mink, Michael.Investor's Business Daily; Los Angeles [Los Angeles] 22 May 2013: A03. Retrieved November 4, 2020, from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1353401867?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo (pg. 18) ↵

- “A Female Civil War Surgeon: ‘How Dr. Mary Is Remarkable.’” Doctor or Doctress? Drexel University. ↵

- Harris, S. M., & Harris, S. (2009). Dr. Mary Walker: An American Radical, 1832-1919. Rutgers University Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/wfu/detail.action?docID=870915 ↵

- “A Female Civil War Surgeon: ‘How Dr. Mary Is Remarkable.’” Doctor or Doctress? Drexel University. ↵

- Mary Walker Stood Tall For Civil War Wounded Dare: Her battlefield courage led to the Medal of Honor - ProQuest . Mink, Michael.Investor's Business Daily; Los Angeles [Los Angeles] 22 May 2013: A03. Retrieved November 4, 2020, from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1353401867?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo (pg. 19) ↵

- Hunt-Hurst, Patricia. "Walker, Mary 1832-1919." In The Federal Era through the 19th Century, edited by José Blanco F., 260-261. Vol. 2 of Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2016. Gale eBooks (accessed November 18, 2020). ↵

- Clinton, Catherine, and Silber, Nina, eds. Battle Scars : Gender and Sexuality in the American Civil War. (Pg. 108-109) ↵