7 How Advertisements Minimize a Women’s Sovereignty Over Her Body

Max Greller

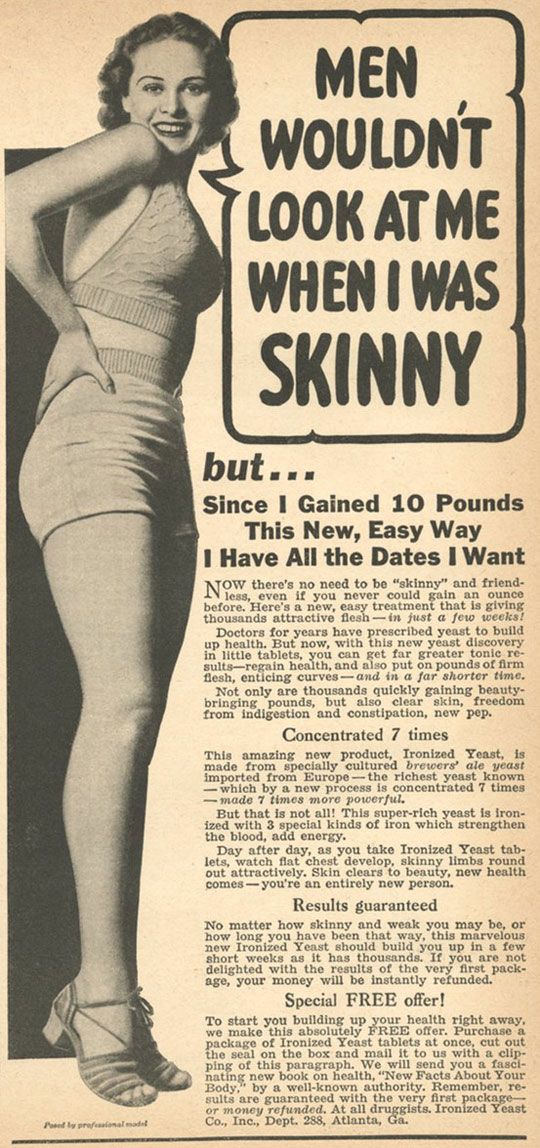

The 1930’s represented a decade of economic disarray during and after the Great Depression. Less capital for the average citizen, particularly women, translated to a lack of sufficient food and nutrition. This caused the average American woman to be much skinnier and resulted in a shift in the ideal form of female beauty; 1930’s media influenced women to focus more on the projection of the ideal woman, instead of emphasizing the need for unity and determination through a time of uncertainty. Unlike the 1920’s where society projected the ideal body shape for women as skinny, the 1930’s marked a decade where physical beauty was characterized with a fuller figure. Because of societal pressure and the cultural obligation to impress men, American women conformed to the standards that were displayed by different advertisements; many companies, particularly the ones that advertised ironized yeast, took advantage of American women’s vulnerable emotional state regarding their own body image. Ironized Yeast company promoted ironized yeast as a solution to obtaining a fuller figure and an increased appetite through higher Vitamin B intake. A 1935 edition of Motion Picture Magazine, an American film magazine that was published for most of the 20th century, displays one of Ironized Yeast Company’s many advertisements.

The advertisement implies that being skinny translates to being friendless; taking the ironized yeast will give the individual woman “attractive flesh” and transform them into “an entirely new person”. The advertisement indirectly conveys that body image comprises a woman’s entire identity. A fuller figure, resulting from the consumption of ironized yeast, will make a woman an entirely new person, meaning a woman should prioritize improving her body image over anything else.

Erving Goffman, an American sociologist who was considered to be the most influential American sociologist during the 20th century, analyzed advertisements and outlined numerous ways in which women were objectified. Goffman classified the portrayal of women in advertisements into six main categories. The advertisement above displays two of these categories: Feminine Touch and Ritualization of Subordination. The model in the advertisement is touching herself which has a sexual connotation because it is almost inviting or allowing the viewer to do the same to her. Similarly, she has a flirtatious pose which further subordinates her and supports the gender norm of women having to constantly please men.[1]

Not only were the ironized yeast advertisements controversial because of the problematic messages and portrayals of women that were conveyed through the different illustrations, but also the product was fundamentally flawed. In 1934, the Federal Trade Commission outlined the cease and desist of Ironized Yeast Company from continuing to advertise on any media platform.[2] The advertisements claimed that the product can end indigestion, nervousness, constipation, sluggishness, and skin eruptions overnight. The company claimed that ironized yeast is a cure for these conditions and for a more ideal body figure; however, the promises that were made were not only exaggerated but false. The Federal Trade Commission decision conveys how ironized yeast does not provide any useful purpose in the treatment of these conditions except when they are produced solely by a deficiency of vitamin B or iron. Even if ironized yeast helped women alleviate the physical conditions summarized above, the advertisements not only exaggerated the benefits and efficiency of the product, but they also directly affected women’s self-conscience by extending societal pressure to adhere to the ideal form of feminine beauty- a societal pressure that manifested over time in every woman’s conscience. Overall, fulfilling societal expectations, as expressed by countless body image advertisements, created a constant amount of gender role stress for women.

During the Great Depression advertisers became desperate; advertisements were targeted towards women in order to convince them that a failure to consume their products would result in loneliness and divorce.[3] Instead of advertisements aiming to combat the deterioration of the economy, magazines and advertisements instead focused on portraying the independence of women as a main reason for familial struggle. Advertisements persuaded women to refrain from challenging gender norms where women were depended on the approval of men. Similarly, advertisements incited apprehension for most women because they communicated how a lack of initiative to look a certain way would result in loneliness. Weight loss advertisements in the 1920’s convinced women that being thin would translate to social and marital stability; however, during and after the Great Depression, advertisements alerted women that being thin was now perceived as unattractive. Women had to constantly manage their body image so that they were not seen as too thin or too overweight, a standard that was not only stressful but also misogynistic.

Although advertisements were used to manipulate women to conform to what was deemed the ideal form of beauty during the Great Depression, the notion of society controlling women’s perceptions of themselves and their acceptance in society (especially by men) can be traced and analyzed beyond the 1930’s. Biopower, a term that was developed by Michel Foucault in the late 1970’s, describes how a society controls and influences large groups of people; biopower often relates to our social and cultural construction of body image. Overtime, society has controlled people’s perceptions of themselves by establishing a constantly evolving depiction of the quintessential body image. Capitalism drives biopower and regulates how individuals make everyday decisions. In her chapter titled “The Roots That Clutch”, Antoinette Burton extends upon Foucault’s theory on societal hegemony. Burton claims, “the modern state has relied on docile bodies for its own sustainability- determining to make them conform if they resisted incorporation into the body politic. In the process, state power has often violated, reshaped and otherwise deformed the body”. [4] The body is a vulnerable concept that capitalism has manipulated. Capitalism therefore values submissive bodies that give into the projection of the ideal body form. Capitalism profits off of the body insecurity of women. It also maintains norms of femininity by coercing women into believing that acceptance and status in society is gained through the conformity to gender norms.

Advertising is a platform in which biopower is often employed. Jean Kilbourne, an activist who is known for her public speaking regarding the portrayal of women in advertising, warns people that they need to take advertising more seriously. She claims that advertising is one of the most powerful socializing forces in our culture and is an inexorable influence. Kilbourne discusses how advertisements contain their own agendas that promote certain values that manipulate individual mindsets and practices. She references a 1970’s United Nations report that discusses gender equality. The report stresses the fact that advertisements perpetuate the concept of women as an inferior class and objectify women by portraying them as sex symbols and illustrating an ideal form of female beauty. Advertisements create a precedent and rigid roles where women who fail to mirror the ideal form of female beauty should feel guilty and implement change at any means necessary.[5]

Early 20th century media surrounded women and infiltrated their minds by targeting their desire to conform to the constantly shifting and ideal form of beauty. Advertisements for ironized yeast were not the only mechanism used to influence women; certain fashion innovations were advertised and had direct ties to women’s body image. The corset, an undergarment that women wore to define their figure, further perpetuated the notion of female imperfection. Corsets were advertised, similar to the ironized yeast, as a means to mitigate women’s “figure faults”.[6] During the 1930’s, ironized yeast and the corset maintained the concept that there was something innately flawed with a woman’s appearance. The stigma of a woman’s body was represented in every facet of her life. Unfortunately, because of advertisements like those for weight gain products and body shaping clothing, women had to continuously monitor and stress about their own body image in order to be appreciated by men and accepted in society.

The ironized yeast advertisement is so problematic because it prioritized societal expectations and capitalism over the mental and physical well-being of women. Advertising was and continues to be a very powerful and exploitative tool; not only did Ironized Yeast Company prioritize their own capitalistic agenda without considering the negative toll the advertisements would have on women’s perceptions of themselves, but they also created the advertisements during a decade of economic and social chaos. Instead of advertising acting as a unifying force, it further subordinated women and suppressed the freedom and choices they made over their own bodies.

Max Greller is a sophomore at Wake Forest on the pre-business track with an entrepreneurship minor. They are from New York and enjoy public speaking and growing cacti.

- Roxanne Hovland et al., “Gender Role Portrayals in American and Korean Advertisements,” Sex Roles, 53 (2005). ↵

- “Federal Trade Commission Decisions” 19 (1934): 129–39. ↵

- Karen Sternheimer, Celebrity Culture and the American Dream: Stardom and Social Mobility (London, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Group, 2014). ↵

- Antoinette M. Burton, “The Roots That Clutch: Bodies, Sex and Race from 1750” (Routledge, 2013), 511-522. ↵

- Kilbourne, Jean, Killing Us Softly - Advertising’s Image of Women, 1979, https://wfu.kanopy.com/video/killing-us-softly. ↵

- Jill Fields, “‘Fighting the Corsetless Evil’: Shaping Corsets and Culture, 1900-1930,” Journal of Social History 33, no. 2 (1999): 355–84 ↵