15 A Gay Bibliography

LGBTQ History Made by America’s Librarians

Miranda Fiore

Introduction

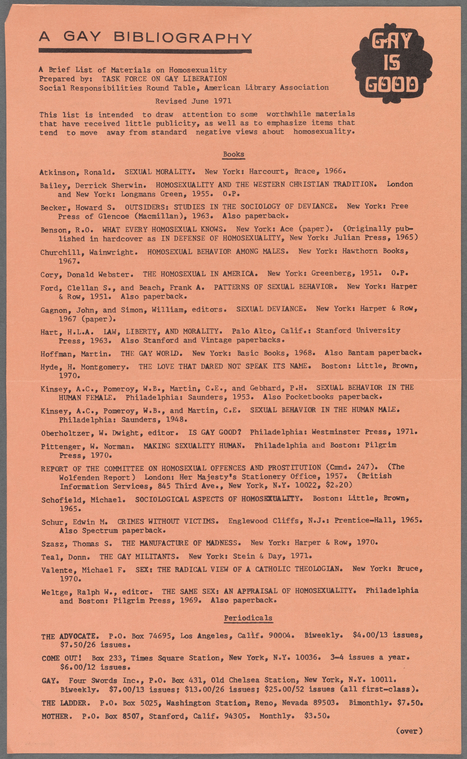

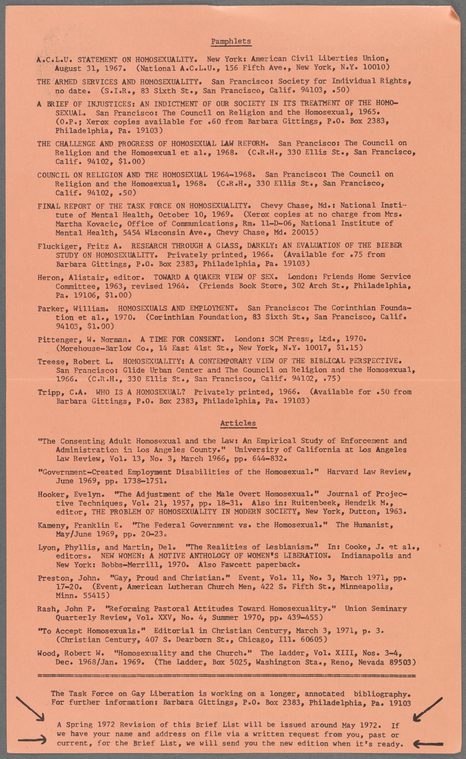

A single piece of paper, typed and double sided, became the calling card of the American Library Association’s (ALA) Gay Task Force: a group of librarians and non-librarian activists committed to changing the negative perception of gays and lesbians in American society. In the early 1970s, discrimination against gay people was widespread and an accepted societal norm. Just a decade earlier, men and women were persecuted, incarcerated, and committed to mental institutions solely because of their sexual orientation. It was not until 1973, that the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality as a “mental illness” from its diagnostic manuals.[1] This makes it all the more significant that in 1970, the ALA, whose members resided in towns large and small across the nation, formed a Task Force on Gay Liberation as a part of their Social Responsibilities Roundtable.[2] To emphasize the word “gay,” and put it first in foremost in the public eye, the group was soon renamed and referred to as the Gay Task Force and is historically significant as the first gay professional organization in the United States. A primary goal of the task force was the creation of bibliographies that would provide wide-spread accessibility to works of non-fiction that portrayed being gay or lesbian in a positive light. The Stonewall Uprising[3]of 1969, had lit a fire under the gay rights movement in the United States, and led to an increase in authorship of gay and lesbian positive topics.[4]Barbara Gittings, an LGBT+ civil rights leader known as the “Mother of LGBT civil rights”, spearheaded the effort to produce the task force’s bibliography.[5] Although she was not a librarian by training, she had spent her youth searching library stacks and shelves trying to find books to help her understand her own sexuality and found mostly depressing and clinical accounts of being gay and an absence of books written by gays for gays.[6] Her own personal history, along with a passion for gay and lesbian activism, motivated Gittings to create A Gay Bibliography, a single piece of paper, with the large and ultimate goal of sparking change in libraries across the nation.

A Gay Bibliography – ALA[7]

To promote the ALA’s newly formed task force, the group’s leaders set up a “Hug a Homosexual” booth at the ALA’s Convention in 1971 to create buzz around the organization and “show gay love, live” by offering same-sex hugs and kisses.[8] At that event, they distributed over 3,000 copies their newly minted bibliography (pictured above). Although they were successful getting the bibliography in the hands of many, change is often met with resistance, and the “hugging” aspect of the booth was criticized (although a popular place to stop and observe) as many convention attendees complained that the “publicity stunt” took time away from noteworthy authors in attendance at the ALA event. Regardless, the task force pushed ahead to continue their important work and persuaded the membership of the ALA to pass a pro-gay resolution at the 1971 convention as well as awarding their first Gay Book Award to Isabel Miller for her novel A Place for Us.[9] The task force also held two programs for the ALA membership to attend: one on the discriminatory and homophobic labeling methodology used by the Library of Congress when classification system and another on homosexual marriage.[10] As the years marched on the attendance Gay Task Force convention programming grew as did their acceptance within the membership of the ALA.

A Gay Bibliography was circulated primarily to libraries across the United States and Canada. As the bibliography grew from its initial 37 entries in 1971, so also did the objective of the publication. In 1971, A Gay Bibliography was grouped into sections for books, periodicals, pamphlets, articles, with the following purpose: “This list is intended to draw attention to some worthwhile materials that have received little publicity, as well as to emphasize items that tend to move away from standard negative views about homosexuality.” [11] By Gittings own accounts, this early publication was put together to reach out to librarians who made the majority of the buying decisions for their libraries and also to reach those in the gay community who were in search of relatable and accurate information about being gay.[12] Between 1971 and 1980, six editions of A Gay Bibliography were produced with the final edition having 563 entries and a distribution of over 38,000 copies. By 1980, the bibliography’s objective had broadened tremendously due to the explosion of published gay and lesbian works of fiction and non-fiction. By now, A Gay Bibliography was a total of 15 pages long and organized by genre, including films and other multimedia. The annotated bibliography’s purpose statement now began: “This selective non-fiction bibliography features materials that present or support positive views of the gay experience, that help in understanding gay people and gay issues, or that have special historical value.”[13]

By 1980, the task force was getting numerous requests for topic specific content listings from both libraries and private organizations. Because of the explosion of LGBT fiction, non-fiction and other library materials, as the Gay Task Force entered the 1980s, it was decided that because of the significant financial and personnel resources used preparing such a comprehensive bibliography on an annual basis, as well as other avenues opening for their advocacy efforts, A Gay Bibliography would be discontinued in its original format after the June 1980 publication.[14] A notable example of the task force’s efforts to broaden their reach includes their publication of Gay Materials For Use in Schools, which listed among other categories, young adult fiction , young adult non-fiction, and audiovisuals, and was distributed to teachers, school librarians, and school counselors in an effort to enable them to guide young adults to resources that supported the exploration of their sexuality in a positive manner.[15]

A group of gay librarians, activists and friends of LGBT rights made important and significant contributions to LGBT+ history by coming together and thinking strategically about how to make the most significant positive impact on the gay community and reach the broadest audience possible in effort to promote understanding and education. The resulting single-page bibliography, at first handed out to other librarians at their annual convention, sparked changed that cannot begin to be quantified in terms of the quality of life and mental health of countless individuals who would now have access to information about themselves as well as relatable fiction that they deserved. The ALA’s Gay Task Force was eventually elevated to “roundtable” status and is currently known as the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender (GLBT) Round Table. The group continues to support the access and information needs of the LGBT+ community.

WORKS CITED

American Library Association. “About SSRT.”Last modified April 30, 2012.http://www.ala.org/rt/srrt/about-srrt.

American Library Association. “ Rainbow Roundtable History Timeline.” Last modified January 25, 2017. http://www.ala.org/rt/glbtrt/about/history.

Gay Task Force. “A Gay Bibliography.” Sixth Edition, 1980. Bibliographies Collection, American Library Association Institutional Repository at the University of Illinois Archives, http://hdl.handle.net/11213/8096.

Gay Task Force. “Gay Materials for Use in Schools.” 1980. Bibliographies Collection, American Library Association Institutional Repository at the University of Illinois Archives. http://hdl.handle.net/11213/8090.

Gittings, Barbara. “Gays in Library Land: The Gay and Lesbian Task Force of the American Library Association: The First Sixteen Years”, Philadelphia, 1990. Reprinted in Daring to Find Our Names: The Search for Lesbigay Library History, edited by Carmichael, James V. Jr., 81-93. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1998.

Gittings, Barbara. “Combating the Lies in Libraries.” In The Gay Academic, edited by Louie Crew, 107-118. Palm Springs, CA: ETC Publications, 1978.

Drescher, Jack. “Out of DSM: Depathologizing Homosexuality.” Behavioral Sciences (Basel, Switzerland). Vol. 5,4 565-75. December 4, 2015, doi:10.3390/bs5040565.

Kagan, Alfred. Progressive Library Organizations – A Worldwide History. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co, Publishers, 2015.

Task Force on Gay Liberation. “A Gay Bibliography.” Second Edition, 1971. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed November 16, 2019. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/1ceb5770-a73a-0137-4739-13b3e7d430d0.

IMAGES CITED

“Isabel Miller and Barbara Gittings at the “Hug a Homosexual” Booth.” Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed November 16, 2019. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-961b-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Villet, Grey. “Gay Rights Event.” 1971. The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images. Image 15 of 15. https://time.com/3507166/silent-no-more-early-days-in-the-fight-for-gay-rights/.

Miranda Fiore is a freshman at Wake Forest University and hopes to major in Psychology and minor in Neuroscience and Entrepreneurship.

- Drescher, Jack. “Out of DSM: Depathologizing Homosexuality.” Behavioral Sciences (Basel, Switzerland), Vol. 5,4 565-75, December 4, 2015, doi:10.3390/bs5040565.The manual used to categorize psychiatric conditions within the health care profession is called Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Up until the APA’s change in 1973, homosexuality was categorized in the DSM as a mental illness. ↵

- American Library Association, “About SSRT,” Last modified April 31, 2012, http://www.ala.org/rt/srrt/about-srrt. In 1969, the ALA established the Social Responsibilities Roundtable, a special unit to help democratize the membership of the ALA and support progressive ideas. The group focused on human and civil rights and other important social issues and worked to “promote social responsibility as a core value of librarianship”. ↵

- The Stonewall Uprising took place in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City on June 28, 1969, after a known LGBT bar was unexpectedly raided by police. As a result, the LGBT community took to the streets of NYC and riots ensued in for six days. The Stonewall Uprising took LGBT activism to a new and previously unseen level and led to the formation of many new LGBT activist organizations. In 2016, President Obama designated the Christopher Street area of Greenwich Village (including the Stonewall Inn), a national monument for its place in the history of LGBT equality. ↵

- Barbara Gittings, “Gays in Library Land:The Gay and Lesbian Task Force of the American Library Association: The First Sixteen Years,”reprinted in Daring to Find Our Names: The Search for Lesbigay Library History, ed. James V. Carmichael Jr. (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1998), 84. ↵

- Barbara Gittings (1932-2007) is often referred to as the “Mother of LGBT civil rights” for her involvement in numerous gay and lesbian civil rights educational efforts and protests that began in the 1960’s and continue to this day. A few of many of Gittings accomplishments include, lobbying the American Psychiatric Association for the de-classification of homosexuality as a mental illness, editor of The Ladder, a lesbian national publication from 1963 – 1966, and leading and participating in the first picket of the White House in 1965, to call attention to homosexual rights. ↵

- Barbara Gittings, “Combating the Lies in Libraries”, In The Gay Academic, ed. Louie Crew (Palm Springs, CA: ETC Publications, 1978), 107-118. ↵

- A Gay Bibliography, 2nd edition, Gay Task Force of the American Library Association, June 1971. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, New York Public Library Digital Collections, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/1ceb5770-a73a-0137-4739-13b3e7d430d0. ↵

- Gittings, “Gays in Library Land: The Gay and Lesbian Task Force of the American Library Association: The First Sixteen Years”, 84. In Gittings’ first person account, she described the Hug a Homosexual booth as being “ogled” while 8 members of the Gay Task Force hugged and kissed in a display of gay and lesbian affection. ↵

- A Place for Us was a historical fiction novel about two women in love in 19th century New England. Written in 1969, and self-published by Isabel Miller, a pen name used by author Alma Routsong, the book was later picked up for publication under the title Patience & Sarah. ↵

- Alfred Kagan, Progressive Library Organizations – A Worldwide History(Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co, Publishers, 2015), 165. ↵

- "A Gay Bibliography", Second Edition, 1971, New York Public Library Digital Collections ↵

- Gittings, “Gays in Library Land: The Gay and Lesbian Task Force of the American Library Association: The First Sixteen Years”, 87. ↵

- Gay Task Force, “A Gay Bibliography,” Sixth Edition, 1980, Bibliographies Collection, American Library Association Institutional Repository at the University of Illinois Archives, http://hdl.handle.net/11213/8096. ↵

- Gittings, “Gays in Library Land: The Gay and Lesbian Task Force of the American Library Association: The First Sixteen Years”, 88. ↵

- Gay Task Force, “Gay Materials for Use in Schools,” 1980, Bibliographies Collection, American Library Association Institutional Repository at the University of Illinois Archives, http://hdl.handle.net/11213/8090. ↵