3 Laundry: Eroticism in Mundane Activity

Olivia Thonson

Introduction

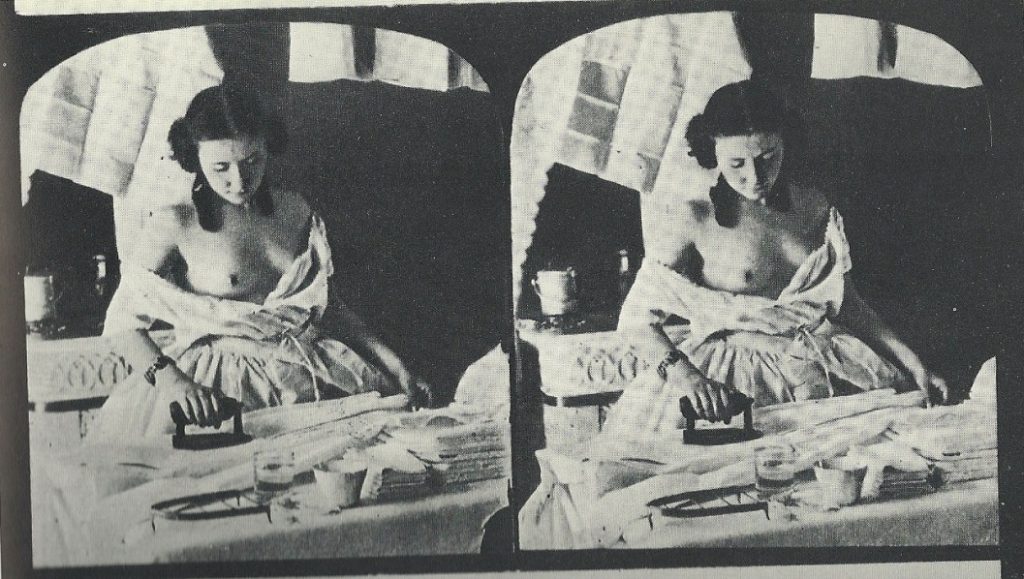

This stereograph[1] holds high cultural significance and value. It’s not famous nor is it well-known; however, the purpose behind the stereograph demonstrates implicit and explicit societal messages of the time period. The image was included in the book Nus d’Autrefois[2], a collection of 19th-century French pornography and erotica. The dress the woman is wearing, her tight corset, hairstyle, and loose sleeves, as well as the objects pictured, indicate this stereoscopic image was taken during the Victorian Era in the early 1860s. In the foreground, there is a young woman ironing laundry, her dress has fallen off of her shoulder and her breast is exposed. Behind the woman, a hanging cloth is visible as well as an oven with a kettle sitting on one of the burners. The longer exposure time insinuates the photograph was posed and most likely intended for the distribution of pornographic material. During the Victorian era, the technological advancements of photography contributed to a rise in the development and distribution of erotica. Due to this phenomenon, there was a shift in laws and norms regarding the censorship and dissemination of suggestive art. Through analyzing the woman’s posing and her mundane tasks, information concerning the role of gender, issues of socio-economic class, as well as a dominant power hierarchy between the sexes in Victorian society become evident.

Stereography and Erotica

The stereoscope was developed in the late 1830s and marked an important technological advancement for photography. Stereoscope images consisted of two daguerreotypes[3] or another form of a photographic process, taken from slightly different angles. Through the binocular vision, two lenses on the stereoscope merge the photograph into one three dimensional image. However, the stereoscope did not just have a technological or scientific impact, it demonstrated a new social development in photography and had an unquantifiable effect on the way people in the Victorian era saw the relationship between the senses, especially touch and vision.[4] The stereoscope gained commercial prominence during the 1850s after scientist David Brewster improved the design, creating a handheld device, which was able to display photographs. The stereographs ranged from travel to staged views and after the development of the wet collodion photography process, prints were affordable, costing only pennies. This allowed middle-class families the ability to travel virtually. The stereoview quickly became a household product and there was a new emphasis placed on visual culture.[5] The French poet Charles Baudelaire[6] described the prevalence of stereoscopic pornography as “a thousand hungry eyes…bending over the peep-holes of the stereoscope, as though they were attic-windows of the infinite.”[7] Similarly to the advent of photography, pornography and erotica became popular with stereography. For viewers, many believed that stereoscopes merged their senses, as they were essentially looking at an optical illusion. Erotic photographs began to be produced in large quantities to fit the new medium.[8]

Today, the study and analysis of Victorian and other 19th-century pornography are rarely found as many early images have not been disseminated or preserved within the art community. There were commonly three categories of 19th-century nude photographs. The first and least morally scrutinized image was the academic nude. These were nude photographs for academic use and study. The other two categories were for pure erotic sensation: eroticism in mundane activities and overtly sexual images. The overtly sexual images were not distributed by studios and sold on an almost “underground” pornographic market in order to disseminate images without the French government knowing. The less overt, and erotic photos, like the primary source pictured above, were posed.[9] In this stereoscope, the woman’s breast is in the center of the image and is illuminated, intentionally drawing a voyeuristic gaze upon her figure. The overall whiteness of the image draws attention to her skin tone. She is pictured washing and ironing clothes which is undoubtedly a domestic duty. There is not only a gendered dynamic to this photography, but it also demonstrates the classist and patriarchal power structure of 19th-century French Victorian society. The stereoscope, making the image three-dimensional offers a different dimension of realism, accentuating the woman’s breast and figure as well as her mundane task.

Victorian pornography was a product of culture, politics, and customs of the time period. However, erotic material characterized as anything from posed eroticism in mundane activities to overtly sexual images were placed under judicial surveillance in both France and Britain. In France, a specific police unit was created and tasked to monitor the distribution and creation of erotic and pornographic photographs. The Dossier BB3[10] was used by authorities to help find those involved with the distribution of pornography. The police are responsible for the prosecution of well-known photographers and models between 1855 and 1868.[11] The censorship on erotica and pornography did not just include photography, but also famous pieces of artwork such as Olympia by Manet.[12] Yet, although the police had a unit that served for over thirteen years and the Dossier BB3 survived, there are very few documents from that time period that remain. In Britain, the House of Commons passed a law that banned street and cheap pornography, leaving expensive erotic books that only the upper class could afford. While the laws and government response to pornography differed based on geopolitical borders, the response against Victorian-era photographic and especially stereoscopic pornography was tied primarily with the debate around purity and class issues.[13] Although the medium of erotica and pornography has changed between centuries, and even decades, the Victorian era paved the way for the erotic material which exists currently today.

When looking at this primary source and analyzing it through an American feminist perspective, one could conclude that the woman in the stereoscope was suppressed by patriarchal forces and made to stay at home and work only within the household. Thinking about it this way, one would draw their conclusions based on the 1950s in American society[14], where women were relegated to the domestic sphere and purely secretarial jobs. This is demonstrative of the change around the analysis and study of the roles of gender. Looking at the primary source, in the specific context of its time period and geographic location, however, it would insinuate a message not only about gender and patriarchal relationships but about class. In 19th century Victorian France, laundry was a task that middle to upper-class wives would not do as it was reserved for someone of lower socioeconomic status, like a laundress or a housemaid. Thus, men could potentially look at this image through a status of superior power and extrapolate that this woman is not only there for doing laundry, but to satisfy their sexual needs or wants as well. The power relationship between the figure and the observer demonstrates that the female body is there for the sole reason to be objectified. There were power dynamics and relationships within the laundry industry in general. Middle to upper-classmen would look at working women and lower-class women in order to satisfy a certain sexual desire. In 19th century Paris, the laundry industry employed around twenty-five percent of the female workforce.[15] The occupation of a laundress signified being in a lower socio-economic class. Victorian society, especially those in the middle class, began to create and shift pornography to be centered around class hierarchy: the occupation of laundresses at the center of it. The penny fiction periodical chroniques scandaleuses became a staple of Victorian pornographic and erotic culture. Through this popular middle-class publication, the lower class and lower class occupations, such as laundresses, began to be associated with loose morals and heightened sexual promiscuity. Due to these stereotypes, the working class became the center of Victorian sexuality.[16] However, the lower and working classes never made the decisions, their bodies and figures, like the woman in the stereoscope, existed for the sexual and labor exploitation by the middle and upper class.[17]

Many French artists played off the idea of a promiscuous working class and created erotic art centered around the idea of a sexual affair with or the sexual promiscuity of a laundress. Novelist Emile Zola published L’Assommoir[18] in 1877. The main character, a poor laundress was characterized by her lack of morals and her sexual promiscuity due to her patriarchal working structure.[19] In Octave Uzanne’s Femme à Paris[20], he wrote that laundresses and ironers “have a shocking reputation for folly and grossness…[they] descend sometimes to the lowest forms of prostitution…”[21] Similarly, in some of Edgar Degas’[22] work, he also depicted laundresses in his artwork, usually in an urban environment, mirroring the setting of the stereoscope image. In addition, Degas’ paintings had erotic and pornographic undertones in which the women subjects can be analyzed as they were open to sexual advances.[23] These artists and writers, like the rest of the middle to upper-class Victorian society, viewed laundresses as objects for over-sexualization and scrutiny. Their work only furthered the classist stereotypes and hierarchy which existed.

While at first, the photograph does not seem like an overt important cultural relic, the subject matter demonstrates the cultural significance of this erotic stereoscope to 19th century Victorian France. Although an inherently mundane task, laundry, and laundresses became a symbol of sexual promiscuity. This stereoscope demonstrates that it was not only an issue of gender but one of class, as the middle to upper class sexualized and took advantage of those in a lower socioeconomic status. While posed, this stereoscopic pornography furthered the stereotype of French laundresses, promoted gendered power struggles, and capitalized off of inherently perverted male voyeurism.

Olivia Thonson is a second year at Wake Forest University majoring in Political Science and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies with a minor in bioethics.

- A stereograph image includes two nearly identical photos that when viewed in a stereoview, creates a three-dimensional image. ↵

- Nus d’Autrefois is a collection of 19th-century French pornography and erotica edited by Marcel Bovis François Saint-Julien and published by Arts et Metiers Graphiques in Paris in 1953. It includes a variety of subjects and different styles of photography. ↵

- Daguerreotype is the first photographic process which used chemicals and a light-sensitive camera to create a one time positive. It was created by Louis Daguerre and introduced to the international scene in 1839. However, with the invention of cheaper and more accessible methods, the daguerreotype quickly became a dated technology. ↵

- John Plunkett, “‘Feeling Seeing’: Touch, Vision and the Stereoscope,” History of Photography 37, no. 4 (November 1, 2013): 389–96, https://doi.org/10.1080/03087298.2013.785718. ↵

- Schools, toys, photographs, and news began to shift to use stereoscope imagery as a tool for education, creating a culture around vision. ↵

- Charles Baudelaire is a very well-known poet from the 19th century. His work had an influence on modernism as well as the production and structure of poetry entirely. ↵

- Clive Thompson, “Stereographs Were the Original Virtual Reality,” Smithsonian, accessed November 17, 2019, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/sterographs-original-virtual-reality-180964771/. ↵

- Isobel Crombie, “Private Pleasures: An Example of French Photographic Erotica | NGV,” accessed November 17, 2019, https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/private-pleasures-an-example-of-french-photographic-erotica/. ↵

- Crombie. ↵

- The Dossier BB3 is a 303-page handwritten document about the production of pornography and erotic images. It holds confiscated stereoscopes of overtly sexual photographs, but also academic nudes, in which artists sold pornography under the guise that it was for education. It also detailed arrest histories. ↵

- Colette Colligan, “Stereograph,” Victorian Review 34, no. 1 (2008): 75–82. ↵

- Thomas B Hess and Linda Nochlin, Woman as Sex Object; Studies in Erotic Art, 1730-1970 (Alvin Garfin, Newsweek, Inc, 1972). ↵

- Kathleen Frederickson, “Victorian Pornography and the Laws of Genre,” Literature Compass 8, no. 5 (2011): 304–12, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-4113.2011.00800.x. ↵

- When analyzing gender, many tend to think of and discuss stereotypical 1950s American gender roles. The woman controlling the domestic sphere (raising children, cleaning the house, doing the laundry), and the man as the breadwinner. This would skew the analysis of the stereograph as it is not about domesticity, but about power structures and classism. ↵

- “Women Ironing » Norton Simon Museum,” accessed November 18, 2019, https://www.nortonsimon.org/art/detail/M.1971.3.P/M.1979.17.P. ↵

- Allison Pease, Modernism, Mass Culture, and the Aesthetics of Obscenity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000). ↵

- Pease. ↵

- L’Assommoir was a twenty-volume series by Emile Zola about the working class, poverty, and alcoholism in Paris. The novel portrays his viewpoints on social and moral determinism and placed the blame directly on the low-income people, rather than the political and economic policies of the time. ↵

- Jaimee Grüring, “Dirty Laundry: Public Hygiene and Public Space in Nineteenth-Century Paris,” n.d., 317. ↵

- A popular history of France during the time. ↵

- Eunice Lipton, “THE LAUNDRESS IN LATE NINETEENTH‐CENTURY FRENCH CULTURE: Imagery, Ideology, and Edgar Degas,” Art History 3, no. 3 (September 1980): 295–313, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.1980.tb00080.x. ↵

- Edgar Degas was a French artist who lived from 1834-1917. Degas was born into a wealthy family and had a complete education of the classics. He is very well-known for his sculptures and drawings of dancers. He is known to be one of the creators of Impressionism. Yet, he continually referred to himself as a realist. Degas also liked to draw laundresses and people of a lower class. ↵

- Grüring, “Dirty Laundry: Public Hygiene and Public Space in Nineteenth-Century Paris.” ↵